Introduction

Delirium is a serious, acute and complex neurocognitive condition that precipitated by an acute event such as infection or surgery. Delirium occurs in around one in five hospitalised patients.1 It is characterised by acute changes in attention, awareness and cognition and affects memory, language, visuospatial ability, orientation and perception.2 Delirium is associated with multiple adverse clinical outcomes, including high levels of patient and caregiver distress, significant morbidity and mortality, impairment of activities of daily living and substantial costs to the healthcare system.3–6

Despite the substantial morbidity and mortality of delirium, knowledge of its pathophysiology is mainly hypothetical, with some underpinning empirical data supporting theories, including involvement of inflammatory systems, neurotransmitter alterations, disruption of circadian rhythm, and glucose metabolism.7 Thus, biomarker studies are crucial to accelerate our understanding of delirium biology leading to potential therapies. A biomarker is a biological molecule found in blood, other body fluids, or tissues that is a sign of a normal or abnormal process or a condition or disease.8 Although there are an increasing number of pathophysiological studies in delirium, results have been inconsistent. This means it is challenging to elucidate biomarker correlations and further infer pathophysiological pathways associated with delirium hindering the subsequent development of targeted therapies.9

Systematic reviews synthesise results from multiple primary studies and are considered the highest level of evidence. Such knowledge synthesis is impeded when primary studies are inadequately reported.10,11 Guidelines emerged in the mid-1990s to counteract widespread deficiencies in reporting published research studies. For example, two independent initiatives to improve the quality of reports of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) led to the development of the CONSORT (CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials) statement, first published in 1996 is now one of the most well-established reporting guidelines in health research.12 The CONSORT statement led the way for developing a multitude of reporting guidelines in multiple journals.13 Reporting guidelines help researchers to meet specific standards by providing a checklist of items for best practice reporting.14

Reporting guidelines with relevance to biomarker studies currently exist. These are: the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) for reporting observational studies10; reporting guidelines for fluid markers in neurologic disorders15; the STARD (STAndards for the Reporting of Diagnostic accuracy)12; and the REMARK (REporting recommendations for tumour MARKer prognostic studies).16 However, these reporting guidelines were not explicitly configured for delirium biomarker studies and no previous work has investigated how they may be modified to inform optimal delirium biomarker research. Special configuration for delirium biomarker studies is crucial as delirium often occurs in the context of other illnesses with overlapping pathophysiological processes. Hence the biomarkers of the other diseases may be inaccurately identified as delirium biomarkers, meaning a binary association is insufficient.

In 2020, we published preliminary recommendations for a reporting guideline for delirium biomarker studies.17 This current paper reports on a follow-up consensus meeting with an expert panel of delirium researchers to finalise the Reporting Essentials for DElirium bioMarker Studies (REDEEMS) guideline.

Methods

Development of REDEEMS

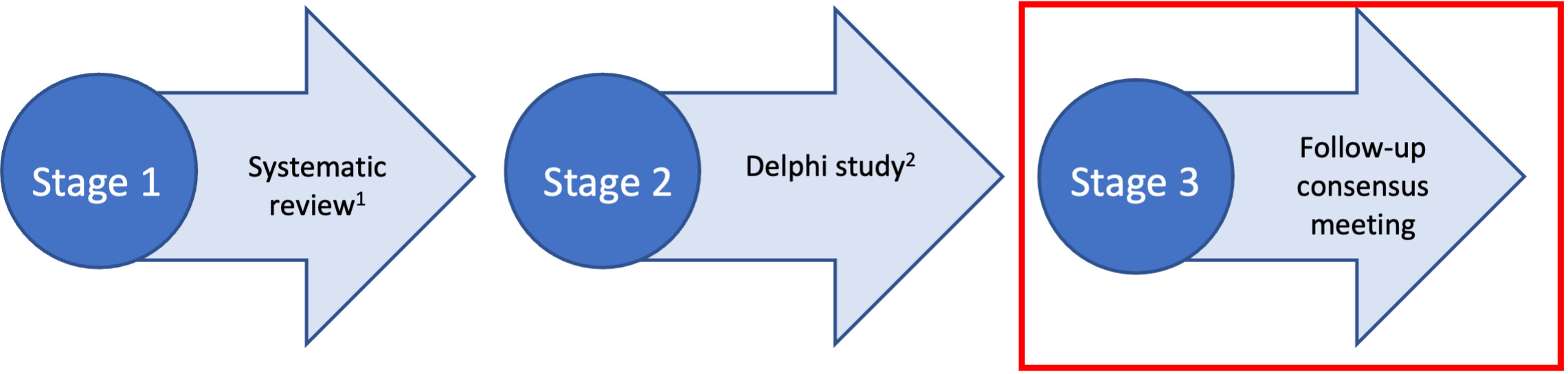

We used a multi-method design to develop the REDEEMS (Figure 1), following methods proposed by Moher et al. (2010).13 This included: a systematic review of the literature identifying a gap in rigorous reporting of delirium biomarker studies9, a three-round Delphi survey17 and a follow-up online consensus meeting. This multi-method and staged process is supported by both Delphi researchers and those experienced in guideline development13,18 and endorsed by the Equator Network.19

The systematic review and Delphi survey have been previously published.9,17 This paper now reports the follow-up consensus meeting in detail.

Participants

Those eligible for the consensus meeting were clinical researchers who had studied delirium in humans including, but not restricted to, biomarkers. Basic science and researchers conducting pre-clinical studies in animals focused on delirium were also eligible. Potential participants were required to have delirium research experience in the last ten years (with no minimum number of years pre-specified). We deemed those who met these eligibility criteria were deemed to have adequate knowledge, expertise and opportunity to make a meaningful contribution to the topic area.

Recruitment

Delphi participants were recruited using a combination of purposive sampling and snowballing.20,21 Membership lists of international Delirium Societies (Australasian Delirium Association, American Delirium Society and the European Delirium Association); colleagues and professional networks; and researchers identified from biomarker journal articles were invited to participate. Snowball sampling was also employed by asking invitees whether they knew any other relevant persons who may be interested in participation.

Participants for the consensus meeting were identified through the Delphi study participant list, and authorship of recent publications in delirium biomarker studies.

Participants who agreed to take part in the consensus meeting were sent an invitation to attend a Zoom meeting one week before the meeting. Participants were asked to sign a written consent form and answer some basic demographic questions to be sent back to the lead author (IAD) before the meeting.

Data collection

We gave meeting attendees the preliminary list of recommendations for reporting of delirium biomarker studies (see Supplementary file 1 and previous publication17). The focus of discussion was on the 16 items that had achieved only borderline consensus (i.e. 70-80%) in the Delphi survey.

A Poll EverywhereTM (polleverywhere.com/) presentation was prepared to provide this information and enable interactive voting with live participant responses and feedback. Group responses were disclosed to participants in real time once all participants had voted, however individual participant votes remained anonymous. Participants were asked to indicate whether or not the item should be included in the guideline (Yes / No) for each item presented. Consensus agreement was determined a priori, based on a majority i.e., ≥50% agreement. Any items which did not achieve consensus agreement were discussed until a consensus opinion was reached. Participants were also asked whether each item was clearly worded and, if not, to provide suggestions to improve the wording. IAD facilitated all voting.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Technology Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (approval no. ETH18-2673).

We stored data transcripts from the meeting on a password-protected computer and removed all participant names. Participant confidentiality, privacy and anonymity were ensured by allocating participant ID codes in the transcripts. Data were only accessible to the lead author (IAD) and de-identified data were only shared with the other authors (MA, AH and GC) for their input into analysis and interpretation.

Results

The consensus meeting was held on June 30, 2020 and lasted approximately 90 minutes. The demographic details of the consensus meeting participants are presented in Table 1.

Of the 16 sixteen items presented to the panel, seven (44%) items were excluded, six (38%) items remained included, and three (19%) items were merged with another item. Most participants believed three items were clearly worded and four needed rewording (Table 2).

For items considered to be unclearly worded, we asked participants to suggest alternative wording in open-text form in PollEverywhereTM. Minor wording suggestions were added for five items. Although two participants voted for item eight not being clearly worded, no alternative wording was added for this item, and it was later agreed that the item should remain unchanged. Of the 7 included items, two items (7c and 8b) were included without any wording changes, four (1e, 1f, 7b and 12b) underwent minor wording changes and three (5b, 13c and 14d) were merged with another item. (Supplementary file 2).

Following the meeting, items were further revised and reworded through email correspondence with meeting participants to ensure clarity of wording aligned with consensus decisions achieved during the meeting. Participants then provided feedback on all items, resulting in the development of Reporting Essentials for Delirium bioMarker Studies (REDEEMS) guideline (Table 3).

Discussion

We present the first reporting guideline for delirium fluid biomarker research. Following the consensus meeting, nine items with 22 sub-items were included in the final version of the REDEEMS.

Our prior systematic9 highlighted a systemic problem of poor quality of reporting of fluid biomarker studies in delirium. Because systemic reporting deficits so clearly hamper progress in the understanding of delirium pathophysiology, a concerted effort is required to standardise the methodology used in delirium biomarker studies if we are to progress this fundamental field of research.

Guidelines are necessary to promote studies that are standardised and reported in a transparent manner to facilitate reliable and consistent interpretation, application and synthesis of study results. Inadequate reporting of studies is well documented. For example, one review of RCT’s conducted in 2006 found that of the 616 trials, only 209 (34%) reported a method of random sequence generation (compared to 21% in 2000) and 156 trials (25%) reported a method of allocation concealment, a slight improvement from 18% in 2000.22 Only 324 trials (53%) defined their primary endpoint, and only 279 (45%) reported a sample size calculation.

Although studies have shown improvements in rigour when using reporting guidelines,23,24 a systematic review examining the extent to which journals encourage reporting guidelines found that only 19 (46%) of the online instructions to authors mentioned reporting guidelines.25

Current guidelines that focus on different aspects of biomarker research include the REMARK, STARD and CONSORT statements, which are used when the focus is on prognostic biomarkers, diagnostic testing or when conducting randomised controlled trials. However, none of these guidelines are specific to delirium. We therefore utilised the REMARK checklist as a framework to guide the development of these preliminary recommendations for guidelines. The final items illustrate areas where specific guidance was deemed useful by international delirium experts to address methodological issues in delirium.

Limitations and strengths

Firstly, the goal of the REDEEMS guideline is to assist authors by providing specific guidance on reporting delirium biomarker studies, not to replicate ‘gold standard’ items included in other existing reporting guidelines. In other fields where a need for additional reporting information has been identified, guideline teams have opted to develop an extension to the existing guidelines, adding specific requirements. Rather than create an extension to an existing guideline like the REMARK checklist, REDEEMS was created as a stand-alone guideline to be used in conjunction with another reporting guideline appropriate for study design. Creating a stand-alone guideline requires an extra layer of effort for authors and reviewers, who must apply a reporting guideline specific to the study design and then use the REDEEMS for reporting the delirium biomarker-specific component. Secondly, the REDEEMS guideline was not piloted before dissemination as proposed by Moher et al (2010).13 However, we addressed clarity and usability of the guidelines through extensive discussions and revisions via the consensus meeting.

Strengths included: the systematic approach to develop the REDEEMS guideline using existing recommendations for developing reporting guidelines in health research.13 At each stage in the process, care was taken to closely align with the Moher framework 13 (except piloting) to minimise the potential for investigator bias. Another strength was the breadth of expertise within the international expert group in both the Delphi study and the consensus meeting. However, we acknowledge that we may not have encompassed all possible perspectives.

Implications for future research and practice

This study proposes the first set of reporting guidelines specific to delirium biomarker studies, which may be refined after experience of their utility in practice. The prior systematic review demonstrated several poor-quality studies that were likely affected by a lack of guidelines for delirium fluid biomarker research. Developing reporting guidelines was essential to improving methodological and reporting rigour, which will increase the potential for future studies to be synthesised through meta-analyses. The REDEEMS guideline will support improved reporting practices and consistency for delirium biomarker studies, thereby permitting more accurate replication and synthesis in the field. The REDEEMS will benefit several groups, including authors, researchers, peer-reviewers and journal editors. Authors of future delirium biomarker studies can contribute to transparent and complete reporting by using the REDEEMS guideline and recommending it to others in the field.

The recommended process for developing reporting guidelines includes the development of an accompanying Elaboration and Explanation (‘E&E’) paper, which the CONSORT group originally undertook to accompany their revised statement.6,7 We are developing this in conjunction with a collaborative team of delirium researchers committed to improving understanding of delirium pathophysiology. The next steps for REDEEMS is dissemination to promote uptake of the guideline and evaluate the influence on improved study rigour and capacity to fully answer study hypotheses.6 Further, since the REDEEMS was not piloted before dissemination, we plan to engage in various stakeholders through delirium societies and delirium journals for further refinement of the guidelines. As new evidence emerges and critical feedback is obtained, the REDEEMS will be updated in the future, such as has occurred for other reporting guidelines such as the CONSORT

This paper presents the first reporting guideline for delirium fluid biomarker studies, developed through a systematic review, a Delphi survey, and the follow-up consensus meeting with international experts in delirium research reported in this paper. We envisage REDEEMS will support more consistent and complete reporting of future delirium biomarker studies and thus contribute to knowledge and knowledge synthesis of delirium pathophysiology.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all Delphi survey and consensus meeting participants for their time, effort and expertise.

Funding

This work was supported by a research award from the Australasian Delirium Association (2019).