Introduction

Delirium affects one in four hospitalized older adults and is linked to prolonged stays, functional decline, caregiver burden, and mortality. Despite these consequences, it is frequently undetected , especially in its hypoactive form, and often misunderstood by clinicians and families.1 Patients describe delirium as a “waking nightmare” of fear, disorientation, and loss of control; yet these experiences are inherently difficult to appreciate from the outside.2 Although frightening or distressing delirium experiences are well described, their true prevalence is unknown due to heterogeneous definitions and reliance on retrospective accounts. Conventional teaching rarely captures this perceptual and emotional reality, leaving persistent gaps in recognition, communication and empathy.3,4 Immersive virtual reality (VR) offers a means to translate abstract knowledge into embodied understanding by recreating the patient’s perceptual world.5–8 When co-designed with those who have lived through delirium, such simulations can evoke empathy and insight. Without this grounding, however, VR education risks oversimplification, emotional overload, or cultural bias, and thus might not facilitate empathy properly.9,10 Moreover, as empathy is a teachable clinical skill, when facilitated thoughtfully, it strengthens communication, diagnostic vigilance, and therapeutic alliance.11 Thus, translating the science of empathy into delirium education requires both innovative media and partnership with patients and caregivers.12,13

Notably, a recent quasi-experimental crossover study in registered nurses found that a brief VR delirium application increased both empathy and knowledge compared with presentation-based training - with the greatest empathy gains when VR preceded didactics - while highlighting the need to monitor for possible desensitisation.14

This study addresses this need by embedding continuous Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) throughout the co-design, implementation, and evaluation of an immersive VR workshop on delirium.15 Guided by the GRIPP2-SF framework and UK Standards for Public Involvement, we assessed the feasibility, safety, and perceived educational impact of a co-designed VR delirium scenario integrating lived experience, structured reflection, and psychological safety.16 Building on pilot work,17 we explored how such experiential learning might bridge the gap between the patient experience of delirium and empathic clinical practice.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a pilot evaluation using a post-experience survey with quantitative and free-text responses. The study took place at the Global Empathy in Healthcare Network Symposium 2025 (“Rehumanizing Healthcare in a Divided World,” University of Leicester). Quantitative data were collected through post-session surveys and qualitative data from structured reflections. We explored feasibility, psychological safety, and perceived educational impact of the VR simulation.

Workshop Structure

The 90-minute session included four sequential components:

-

Introductory overview (~20’): brief presentation on delirium epidemiology, diagnostic criteria, and lived experience to establish a shared baseline.

-

Immersive simulation (~10’): single-user VR experience modelling delirium phenomenology from the patient’s perspective.

-

Immediate post-session survey (~20’): a brief instrument capturing participants’ emotional reaction, cognitive insights, and intended care-related behaviours in response to the simulation. Behavioural intentions referred to planned clinical actions by participants (e.g., speaking more slowly, reducing environmental stimuli, actively including caregivers, and using de-escalation strategies). These intentions were distinct from the simulated patient behaviours (e.g., confusion, sensory overload), which were designed to evoke the patient’s perspective and experiential understanding.

-

Immediate post-session survey (~20’): brief instrument capturing emotional, cognitive, and behavioural intentions (e.g., slower speech, reduced sensory load, caregiver inclusion, de-escalation). Structured reflection (~25’): small-group dialogue translating individual experiences into practical communication and ethical insight.

The framework links emotional immersion with structured reflection, allowing transient reactions to become sustained empathic understanding.

Patient and Public Involvement (PPI)

The project originated at the Dräger Fokustag Delir (Clinic Barmelweid, Switzerland, 2023), where clinicians, researchers, and advocates co-created an empathy-based framework for delirium education. Building on this initiative, four public contributors (a delirium survivor, two family caregivers, and one patient advocate) participated throughout concept development, scenario design, pilot testing, and manuscript review. Their input shaped scenario language, ethical safeguards, and reflection prompts, leading to inclusion of content warnings, opt-out and quiet-space options, and non-stigmatising phrasing.

All PPI activities followed the GRIPP2-SF framework15 and aligned with the UK Standards for Public Involvement.18

Setting and Participants

The workshop was held in a dedicated teaching space with access to a quiet recovery area. Eligible participants from the empathy summit included clinicians, educators, researchers, trainees, policymakers, and caregivers. After the VR experience, participants completed the post-session survey and reflection activities.

Intervention and Safeguards

Participants engaged in a 10-minute VR simulation depicting core features of delirium: fluctuating attention, disorientation, perceptual disturbance, emotional distress, and loss of agency. Two scenarios illustrated contrasting communication approaches with an 82-year-old postoperative patient (“Mr Meier”):

-

Example 1: a rushed, fragmented interaction amplifying perceptual overload and fear

-

Example 2: a structured, empathic exchange incorporating pre-room preparation, single-voice leadership, and gentle reorientation.

Both scenarios were refined through iterative PPI consultation and expert review. Design followed simulation-ethics principles: pre-briefing, informed opt-out, facilitator support, and access to a quiet recovery space.

Example 2 integrated evidence-based communication models (Riess,19 Howick,20,21 CARE framework,22,23 and NICE delirium-prevention guidance24), emphasizing calm tone, simplified syntax, contextual orientation, and patient-first phrasing. Experiencing the scenarios sequentially allowed participants to contrast harmful versus empathic communication and to reflect on how subtle behavioural shifts transform the patient’s perceptual world.

Structured Reflection

After the simulation, participants engaged in a structured reflection to consolidate emotional and cognitive learning. In pairs, they discussed patient and family perspectives, key challenges in delirium care, and system factors such as realism and dignity. Reflections were summarised into thematic categories for analysis.

Survey Instrument and Outcomes

A brief post-session survey assessed perceived impact on empathy, communication, and behavioural intentions. Items were adapted from validated sources (Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy,28 CARE Measure,29 and Delirium Experience Questionnaire30) to suit a brief, interdisciplinary workshop format. Items used 5-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) with open-text options. Adaptations were required because of session length and timing constraints; two educators and two PPI partners reviewed all items for face and content validity. The final composite instrument was tailored for an interprofessional audience and focused on empathy as a concept and in practice, hidden curricula, diversity, and intended clinical and educational actions.

Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis

Quantitative data from Likert-scale items were summarised as means (SD) or medians (IQR), as appropriate. Qualitative reflections were open-coded and inductively clustered into higher-order domains by two authors (MS, TK), with categories refined through in-session member-checking. Because all items were fully completed, no imputation or missing-data procedures were required.

Results

Survey Completion and Participant Characteristics

Participants included researchers (6/15, 40.0%), nurses (5/15, 33.3%), and physicians (4/15, 26.7%). Primary specialties were Law & Medical Ethics (4/15, 26.7%), Geriatrics (3/15, 20.0%), Internal Medicine (3/15, 20.0%), and Public Health/Education (2/15, 13.3%); Family Medicine, Pediatrics, and Intensive Care were each represented once (1/15, 6.7%). Most participants worked in university hospitals (12/15, 80.0%), with the remainder in the Ministry of Health, general practice, or outpatient clinics (1/15, 6.7% each).

Professional experience was generally high: eight participants (53.3%) had over 20 years of experience, and seven (46.7%) had 6–10 years. Prior exposure to VR was limited: none in 11/15 (73.3%), 1–2 sessions in 2/15 (13.3%), and 3–5 sessions in 2/15 (13.3%). Formal delirium training was absent in nearly half (7/15, 46.7%), brief (<1 hour) in four (26.7%), and moderate (~3 hours) in four (26.7%). In the preceding six months, 10 participants (66.7%) had not directly cared for delirium patients, while five (33.3%) had managed 3–5 cases. Prior empathy training was common (10/15, 66.7%). Overall, the sample represented an experienced, interprofessional group with limited prior exposure to VR or delirium-specific pedagogy, an appropriate target population for exploratory empathy education.

Overview of Quantitative Findings

Quantitative results (n = 15) summarised participants’ Likert-scale responses across predefined questionnaire sections (B–G). There were no partial survey submissions; all respondents completed all items. Descriptive statistics (means ± SD or medians [IQR]) and item distributions are reported below, with full item wording in Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figures 1–6. Overall, most items showed median ratings of 4–5, reflecting broad agreement.

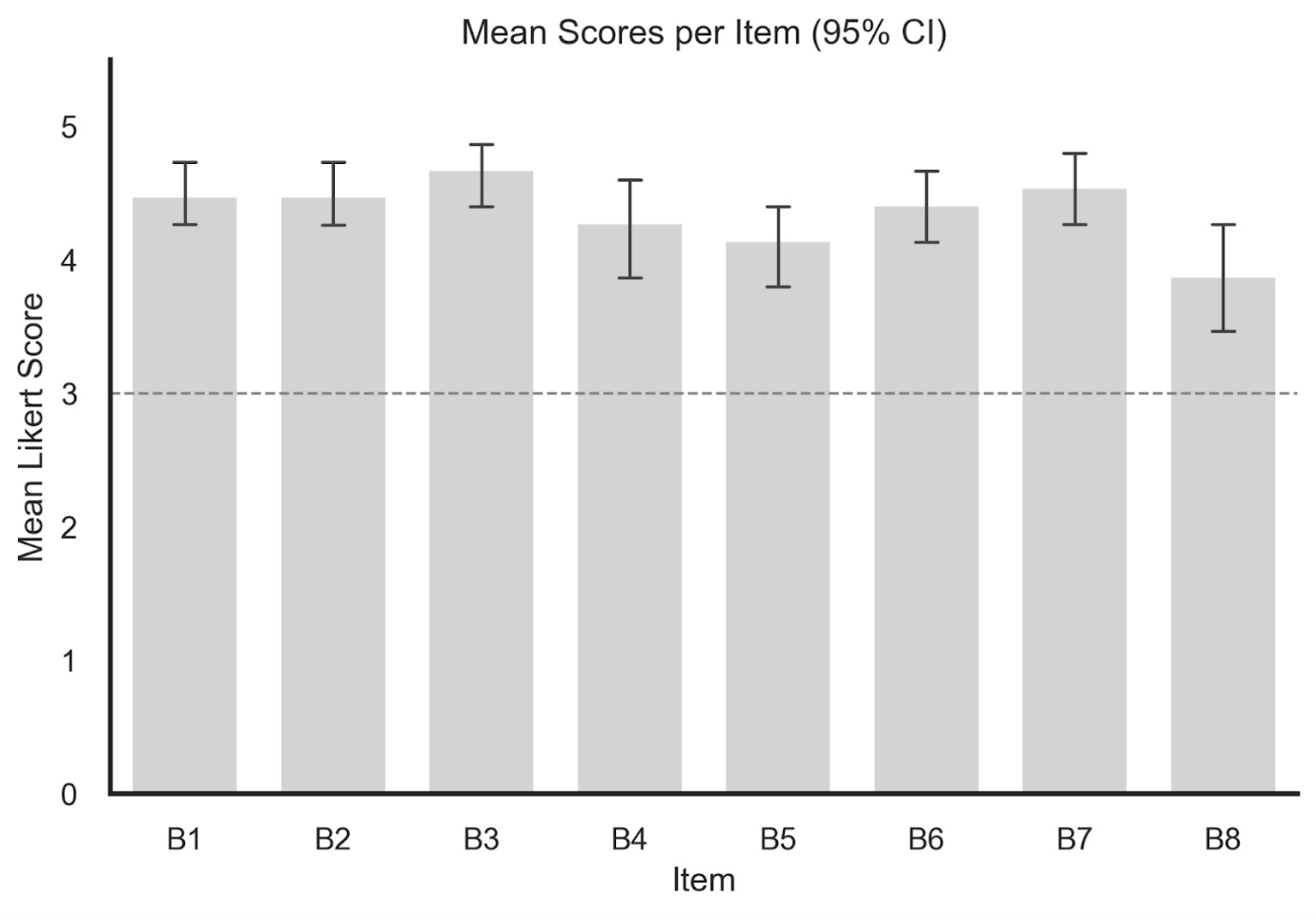

Perceived experience (Section B). Items in this section examined how realistic, immersive, and emotionally intense the VR scenario felt and whether participants perceived it as more effective than traditional teaching (see Supplementary Figure 1). Example items included “The VR scenario felt realistic,” “I felt immersed in the situation,” “The simulation was emotionally intense,” and “VR is better than traditional teaching.” Section-level endorsement was high (mean 4.35 ± 0.33; top-two-box 92.5%). Items on realism and immersion achieved 100% agreement (15/15; 95%; medians 4–5 [IQR 4.0–5.]). Emotional intensity was also highly endorsed (14/15, 93.3%; median 4 [IQR 4.0–5.0]). The comparator item showed greater variability (9/15, 60.0%; median 4 [IQR 3.0–4.5]). These results show that participants perceived strong realism and emotional engagement but were less unanimous about VR’s superiority to traditional teaching.

Empathy constructs (Section C). Items in this section explored cognitive and behavioural empathy, including imagining the patient’s perspective, active listening, emotional attunement, and maintaining empathic boundaries (see Supplementary Figure 2). Example items included “I could imagine what the patient was experiencing,” “I am motivated to listen more carefully to patients,” “I could sense the patient’s emotions,” and “I can connect empathetically while keeping professional limits.” Overall endorsement was strong (mean 4.09 ± 0.39; top-two-box 81.7%). Perspective-taking and motivation to listen were universally endorsed (15/15; medians 4–5). Emotional attunement and boundary-aware empathy showed more variability (≈ 50% agreement; medians 3–4). These results show that participants valued cognitive and behavioural empathy, particularly perspective-taking and attentive listening. Emotional attunement and maintaining boundaries were endorsed less consistently, suggesting greater confidence in observable empathic actions than in affective synchrony. Qualitative reflections echoed this balance, portraying empathy as both disciplined understanding and emotional awareness.

Hidden curriculum and role-modelling (Section D). Questions in this section addressed implicit learning influences: the effect of stress and workload on empathy, the role of senior colleagues, and the impact of positive or dismissive role models (see Supplementary Figure 3). Representative items included “Stress reduces empathy in my team,” “Senior staff attitudes shape team empathy,” “I learn empathy from observing positive examples,” and “Dismissive behaviour reduces my empathy.” Section-level scores were high (mean 4.37 ± 0.25; top-two-box 86.7%). Harms from dismissive role models and the value of positive examples were uniformly endorsed (15/15; medians 5). Stress and senior-staff influence were strongly recognised (≥ 93% agreement; medians 4–5). Distinguishing superficial from genuine empathy showed low consensus (20.0%; median 3 [IQR 2.0–3.0]). These results show that respondents recognised the strong influence of modelling on empathic behaviour, especially the harm of dismissive conduct under stress. Distinguishing genuine from performative empathy proved difficult, reflecting the hierarchical tensions of clinical culture. Open reflections reinforced this dynamic within the “hidden curriculum” of workplace empathy.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (Section E). This section assessed awareness of DEI principles such as risk of ageism, cultural and language sensitivity, stigma, and overlapping vulnerabilities (see Supplementary Figure 4). Example items included “Older adults may be underestimated because of age,” “I should adapt communication to the patient’s background,” “Delirium can be misunderstood across cultures,” and “Different forms of vulnerability can overlap.” Items were positively rated (mean 4.19 ± 0.33; top-two-box 80.8%). Awareness of ageism, communication adaptation, and stigma was universal (15/15; medians 5). More variability appeared for cultural and intersectional items (60–67% agreement; medians 4). These results show that participants showed strong awareness of ageism and communication needs, consistent with person-centred care principles. Greater variability across cultural and intersectional items suggests scope to strengthen cultural humility and inclusivity. Qualitative comments similarly linked empathy to fairness and equity in care delivery.

Intended clinical and educational behaviours (Section F). Items in this section captured intended behavioural change: recognising distress, providing reassurance under pressure, involving caregivers, using de-escalation techniques, and modelling empathy for peers or trainees (see Supplementary Figure 5). Example items included “I will pay more attention to signs of distress,” “I will reassure patients calmly even when stressed,” “I will involve family members more actively,” and “I plan to model empathic behaviour for colleagues.” Behavioral intentions were high (mean 4.42 ± 0.21; top-two-box 82.5%). Recognition of distress, reassurance, caregiver inclusion, and de-escalation reached 100% endorsement. Modelling empathy for colleagues (40%) and practicing empathy under stress (27%) were lower. These results show that participants reported clear intentions to apply empathic behaviours- particularly reassurance and caregiver inclusion. Confidence in modelling empathy for peers or sustaining it under pressure was lower, underscoring the difficulty of maintaining empathy in demanding settings. Reflections described empathy as a skill requiring continuous reinforcement.

Alignment with delirium-care priorities and adoption (Section G). This section evaluated perceived alignment with delirium-care priorities: scenario realism, preservation of dignity and agency, communication relevance, and willingness to recommend or adopt the training (see Supplementary Figure 6). Example items included “The simulation reflected real delirium cases,” “The patient’s dignity was maintained,” “The scenario improved my communication awareness,” and “I would recommend this VR session to others.” Global appraisal was favourable (mean 4.42 ± 0.21; top-two-box 89.3%). Realism, dignity, and communication were uniformly endorsed (15/15; medians 4–5). Transferability for personal teaching use showed more variability (9/15, 60%; median 4 [IQR 3.0–5.0]). All participants recommended implementation (15/15, 100%; median 5). These results show that the intervention aligned strongly with delirium-care priorities, with unanimous endorsement for realism, dignity, and communication. Variability in perceived teaching transferability points to the need for faculty development and institutional support for sustained use. Qualitative data confirmed the convergence of empathy, realism, and clinical relevance.

Qualitative Findings from Structured Reflection

Approximately 50 unique insights were captured in real-time, coded and inductively grouped into three themes (Figure 1):

-

Authenticity and Emotional Credibility: Perceptual distortion generated “safe discomfort,” enabling participants to feel confusion and reframe communication through the patient’s lens.

-

Psychological Safety: Co-designed safeguards (i.e., ethical framing, opt-out options, and access to a quiet recovery space) supported emotional engagement without harm.

-

Equity and System Translation: Participants identified strategies for inclusive and sustainable adoption, such as low-cost roll-outs, caregiver inclusion, and brief team debriefs.

Together, these themes suggest that co-designed affective immersion, bounded by safety protocols, can catalyze reflective communication and sustain empathy while preserving patient dignity.

Discussion

In this pilot evaluation, a co-designed immersive VR workshop on delirium was perceived as realistic, emotionally credible, and educationally meaningful. Participants reported stronger perspective-taking and intent to modify communication, while qualitative reflections highlighted empathy, safety, and system translation as core domains. Collectively, these findings indicate that patient-partnered VR, when grounded in lived experience and structured reflection, can foster empathic understanding and ethical awareness in delirium education. These results are consistent with preliminary pilot findings showing comparable feasibility and perceived empathy improvements.17

Mechanisms of impact

Empathy research shows that emotional activation alone seldom sustains behaviour change; it is reflection that converts it into learning.13 This proof-of-concept study supports a dual mechanism: affective immersion reproduced delirium’s confusion and distress, fostering patient perspective, then structured reflection translated emotion into communication strategies - calm tone, slower pace, environmental control, and caregiver inclusion. Together, they operationalize empathy as both cognitive discipline and relational skill, consistent with experiential-learning and simulation-ethics frameworks emphasizing authentic yet psychologically safe engagement.

Educational and clinical implications

Delirium education can be effective, but it is manifestly challenging and complex.4,31 A specific challenge is that the nature of delirium is such that its symptoms are often invisible, leading to a lack of professional understanding of the patient experience of delirium. We found that co-designed VR helped to make these experiences tangible, transforming abstract symptoms (i.e., disorientation, threat misinterpretation, loss of agency) into relatable sensations. Participants linked the experience to concrete actions that could help stabilize patients, such as simplifying communication and maintaining orientation. These are not new techniques, but fundamental practices re-learned through embodied experience rather than instruction. Sustained behaviour change, however, likely requires longitudinal reinforcement through mentorship, debriefing, or reflective journaling to move from momentary empathy to consistent clinical practice. However, it must be acknowledged that the VR scenario reflects a psychologically distressing subtype of delirium; while clinically important, such episodes are not universal and should not be understood as representative of all delirium presentations

Patient and public involvement

Continuous Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) was integral to this project. Contributors informed scenario language, ethical safeguards, and reflection prompts, ensuring authenticity and emotional protection. Their role evolved from consultation to co-authorship and ethical stewardship, exemplifying how lived experience can shape both design and evaluation. Future work should broaden representation to include marginalized and digitally excluded groups and evaluate engagement quality using structured instruments such as PPEET v2.0 or PEIRS-22.32

Equity and implementation

Scaling VR education raises issues of access and equity. Cost, technological literacy, and institutional readiness can widen disparities if not addressed. Future research should evaluate cost-effectiveness, cultural adaptation, and integration into existing curricula using open-access platforms or train-the-trainer models. Ethical implementation demands pre-briefing, monitoring for cybersickness, and post-session support, particularly for participants with prior trauma. The goal is empathy with protection, emotional credibility without re-traumatisation.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this work include the involvement of an interprofessional participant group and the continuous engagement of people with lived experience throughout development, which helped ensure clinical and experiential relevance. At the same time, the small, self-selected nature of the sample means that the findings should be regarded as preliminary and not generalisable beyond similarly motivated groups. Because participants were drawn from an empathy-focused event, disciplinary representativeness is limited, and caution is warranted when extrapolating the results to broader healthcare populations.

The quantitative findings should be interpreted as exploratory; nonetheless, they showed patterns that were directionally consistent with the qualitative impressions, supporting the feasibility and internal coherence of the VR approach. The focus on acute hospital delirium may restrict applicability to other care settings, underscoring the need for replication in more diverse clinical contexts. As the work constitutes a survey-based pilot rather than a mixed-method or hypothesis-driven study, all interpretations should be made in that light. Finally, the length of the questionnaire may have constrained the richness of free-text responses.

Future directions

Three priorities emerge for subsequent research:

-

Effectiveness and retention - Evaluate whether empathic communication behaviours and patient outcomes improve and persist over time.

-

Implementation and scalability - Assess cost-effectiveness, cultural adaptation, and integration into multiprofessional training programs.

-

Measurement innovation - Incorporate empathy calibration, emotional safety, and inclusion metrics as core outcomes alongside traditional knowledge-based indicators.

Conclusion

This pilot evaluation suggests that an immersive, co-designed VR representation of delirium may offer a feasible and acceptable way to support empathy-oriented learning among motivated participants. By grounding the simulation in lived experience and pairing it with guided reflection, the approach shows early potential to illuminate aspects of the emotional and cognitive disturbance that patients describe, thereby enriching existing educational strategies. These insights remain preliminary: the small, self-selected sample, the focus on a psychologically distressing delirium subtype, and the survey-based design all limit generalizability and indicate that the findings should be interpreted with caution.

Nevertheless, the work illustrates how experiential tools might complement traditional teaching by fostering curiosity, perspective-taking, and reflective practice - elements central to compassionate delirium care. Importantly, technologies such as VR cannot, on their own, humanize clinical practice; their value arises only when embedded within thoughtful pedagogy, patient partnership, and team dialogue. Future studies should therefore test this approach in broader clinical settings, evaluate behavioural outcomes, and integrate principles from implementation science to understand how such experiential methods can meaningfully support everyday delirium care.

Acknowledgments

We thank the PPI representatives, who requested anonymity, for their ongoing support and guidance. Their lived experience input shaped scenario language, safety procedures, and reflection prompts, and materially improved the authenticity and ethical conduct of this project. We acknowledge the contributors to an earlier pilot version of the VR delirium simulation, whose preliminary work informed the present study design.17

Author Contribution

-

Mathias Schlögl: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – original draft, review & editing; Supervision; Funding acquisition.

-

Laura Fontanesi: Writing – review & editing.

-

Arzu Çöltekin: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing; Supervision.

-

Thomas Kunz: Conceptualization; Software; Investigation; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

-

Steven Bourke: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

-

Rasita Vinay: Writing – review & editing.

-

Tobias Kowatsch: Writing – review & editing.

-

Leo Kronberger: Writing – review & editing.

-

Giuseppe Belleli: Writing – review & editing.

-

Virginia Boccardi: Writing – review & editing.

-

Paolo Piaggi: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

-

Vincenza Frisardi: Writing – review & editing.

-

Yuliya N. Yoncheva: Writing – review & editing.

-

Jeremy Howick: Writing – review & editing.

-

Alasdair MacLullich: Writing – review & editing.

Ethics statement

The study was reviewed using a checklist, according to institutional procedures at the FHNW School of Applied Psychology and was classified as not requiring cantonal ethics approval. The study adhered to GDPR requirements. All participants provided written informed consent before participation.

Funding sources

The study was partially funded by Draeger Schweiz AG, FHNW, and Clinic Barmelweid resources.

Declaration of Interests

RV and TK are affiliated with the Centre for Digital Health Interventions (CDHI), a joint initiative of the Institute for Implementation Science in Health Care, University of Zurich, the Department of Management, Technology, and Economics at ETH Zurich, and the Institute of

Technology Management and School of Medicine at the University of St Gallen. CDHI is funded in part by the Swiss health insurer CSS, the Austrian health care provider (and corporate start-up of UNIQA) Mavie Next, and the Swiss investor MTIP. TK was also a co-founder of Pathmate Technologies, a university spin-off company that creates and delivers digital clinical pathways. However, neither CSS, Mavie Next, Pathmate Technologies nor MTIP engaged in this study. Furthermore, TK has neither shares of Pathmate Technologies nor any formal role in the company. SB is the owner and founder of PersonalPulse. SB is a fellow of EUPATI foundation. All other authors declare no competing interests.