Introduction

Delirium is an acute neurocognitive condition experienced by up to 30% of severely unwell adults and children in hospital.1,2 Delirium is characterised by acute and fluctuating changes in awareness, attention, and cognition3,4 and can be caused by numerous medical and environmental factors. Patients can feel distressed during and after the delirium, with common emotions being fear, anger and shame.5 Family carers can feel scared for the person’s safety and for their own and uncertain about if or when the delirium will resolve6; and delirium care is challenging and complex for nursing, medical and allied health staff.7

Distress related to delirium is emerging as an important but under-researched concept. The American Psychological Association defines distress more generally as a negative stress response, occurring where individuals become overwhelmed by stressors (such as perceived threats or demands).8 Distress can pose a serious health risk for individuals, causing physical and psychological harms.8 A recent narrative review examined distress in delirium for patients, their carers and hospital staff.9 The authors used a broad conceptualisation, incorporating related anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, and concluded that supportive interventions require more thorough understanding and clinical knowledge of delirium-related distress. Similarly, a systematic review of delirium-related distress in the intensive care unit (ICU) found delirium-related distress was a holistic experience, encompassing “emotional, cognitive, physical, relational, spiritual and situational dimensions” (p. 11).10 The authors here concluded that a consensus definition would inform the development of outcome measures for future research. Emotional distress is included in new core outcome sets (COS) for delirium in intensive, acute, palliative and residential aged care settings.11–14 The most recent publication in this suite of work described a consensus study of measurement methods for the COS pertaining to delirium trials in intensive care units (ICUs); in this, consensus on anxiety and depression measures was achieved but not for acute stress and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.12 The authors also noted that distress in delirium went beyond just anxiety and depression.

Thus, to date there is no consensus definition of delirium-related distress, no complete and cohesive understanding of its nature or mediators, and no consensus on its measures. Undertaking a concept analysis of delirium-related distress would build understanding and support the development of a definition, enabling future research to develop specific assessment and outcome measures and interventions. The objective of this scoping review was therefore to review published literature on delirium-related distress using the concept analysis method15 to develop a cohesive understanding of this concept that informs future research.

Methods

The study was a scoping review16 and concept analysis,15 with an a priori protocol registered on the Open Science Framework.17 The review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR).18

The scoping review methodology was chosen to enable a comprehensive overview of available literature. Concept analysis was undertaken to clarify the defining characteristics of delirium-related distress by reviewing available literature. Here, ‘attributes’ were the core distinguishing features of delirium-related distress15; ‘antecedents’ were factors occurring before it15; and ‘consequences’ were outcomes.15 Empirical referents, or ways that delirium-related distress is measured, were also identified; as were protective factors, i.e. those that reduced or relieved delirium-related distress.19Finally, we constructed four cases (model, borderline, related and contrary) to further clarify the concept.15

Search Strategy

The search was conducted in MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo and Scopus. The first search occurred on 19 June 2023 and updated on 14 October 2024. The search terms used for Scopus were delirium; alcohol withdrawal delirium; psychological distress; anxi*; depress*; fear; worry; patient safety; pain; shame; guilt; psychological stress; agitation; restlessness; hospital*; inpatient*; palliative; critical care; intensive care. The search strategy was built with the help of a university librarian and used MeSH (Medical Subject Heading)20 terms wherever possible to include studies that may have used different terminology for the same concepts. For example, MeSH terms were used for delirium and psychological distress in all database searches.

Sources of evidence screening and selection

Qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies were eligible if published in English since 1980 (when delirium was added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual21) and focused on patient, carer or staff experiences of delirium-related distress in any hospital setting. Screening used Covidence Systematic Review Software. Duplicates were removed. Abstracts were reviewed by the lead author, with 20% double-checked by co-authors.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were extracted by the lead author into an Excel spreadsheet, which was reviewed by the authorship team. Data extracted included study aims, methods, demographics and results, and the antecedents, consequences, attributes, protective factors and empirical referents of delirium-related distress. Data were synthesised according to the concept analysis headings, including protective factors and empirical referents, and case studies were constructed.

Results

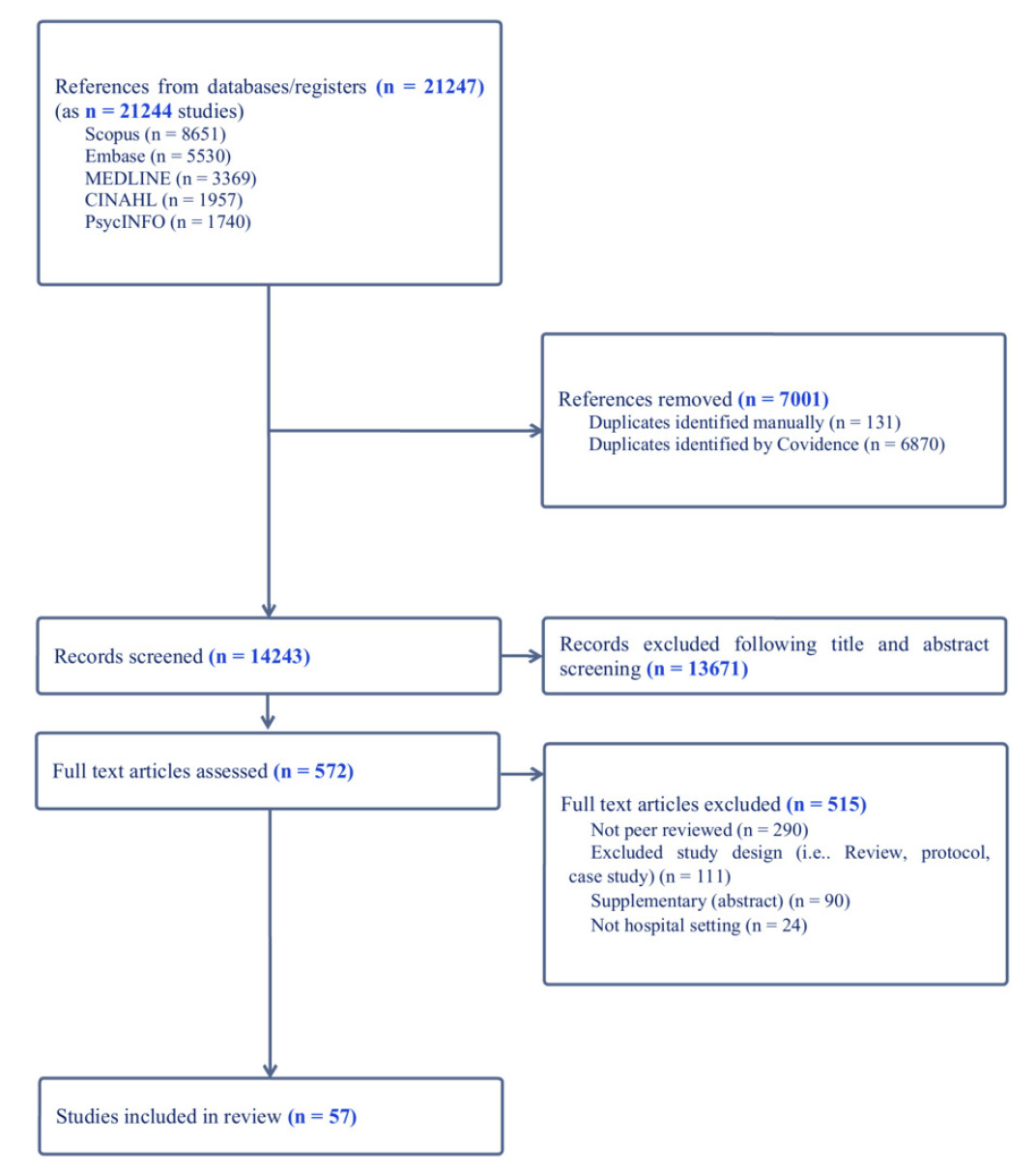

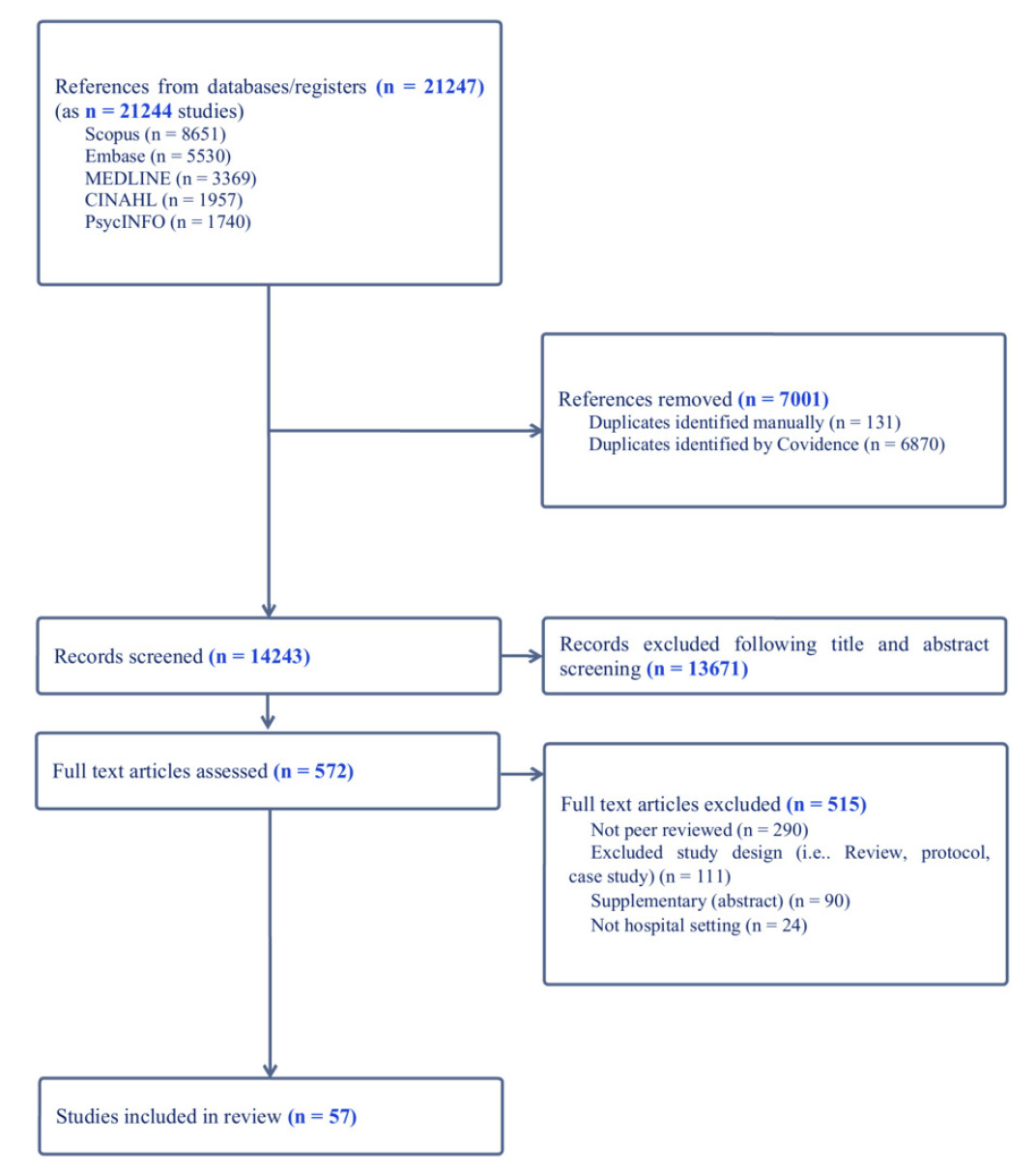

From the 14,243 titles and abstracts screened, 572 had full text review, and 57 articles were included for analysis (Figure 1). Tables 1a, 1b and 1c present the characteristics of included studies, categorised as quantitative (n=23), qualitative (n=27), and mixed methods (n=7) studies. Fourteen studies were published in America,22–35 13 in the United Kingdom,12–14,36–45 seven in Australia,46–52 five in Canada,53–57 four in Japan,58–61 three in Sweden,62–64 and Denmark,65–67 two in China,68,69 Portugal,70,71 and Poland,72,73 and one each in India,74 Taiwan,75 Italy76 and Korea.77

Figure 1.PRISMA Diagram

Table 1a.Characteristics of included studies (Quantitative, N=23)

| First author, date (country) |

Aim |

Methods |

Setting |

Population: N, age, % women |

Results |

| Breitbart 2002 (USA) |

Examine experience of delirium in hospitalised patients with cancer, and describe frequency of recall |

Survey |

Cancer |

P: 10, 19-89, 48%

FC: 75, N/R, N/R

C: 101, N/R, N/R |

P: 100% of patients with mild delirium were able to recall, 55% with moderate and 16% with severe. Distress was related to perceptual disturbances and severity of delusions.

FC: 76% reported severe distress.

C: 73% reported severe distress related to patient dehydration, systemic infection, perceptual disturbances, sleep wake disturbance and delirium severity. |

| Buss 2007 (USA) |

Relationship between caregiver-perceived delirium and rates of psychiatric disorders |

Survey |

Cancer |

FC: 200, 20-83, 76% |

Caregivers who reported caregiver-perceived delirium were 21x more likely to have symptoms of generalised anxiety, which was related to higher family carer burden |

| Aggar 2024 (AUS) |

To evaluate a prevention toolkit to support partnerships between carers and nurses to prevent and manage delirium |

Pre-post intervention |

General Hospital Ward |

FC: 56, M=65, 68% |

The PREDICT toolkit increased carer delirium knowledge from admission to discharge d=1.1. Of the carers who intended to use PREDICT, 72% did use it. Distress scores, measured by the DEL-B-C and K10 did not change from admission to post-discharge. |

| Han 2023 (USA) |

Identifying modifiable in hospital factors associated with global cognition, PTSD and depression at 12 months |

Survey |

General Hospital Ward |

P: 203, M=55, 46% |

Of all participants, 56.7% had delirium during hospital admission. Delirium was associated with higher PTSD symptom severity, and worsening depression symptom severity. |

| Hosie 2021 (AUS) |

To investigate the influence of recent studies and other factors on clinicians’ delirium treatment practice and practice change in palliative care and other specialties |

Survey |

All settings, including hospitals |

C: 475, 50-59, 83% |

55% of those surveyed reported antipsychotic use, mostly for patient distress (79%). |

| Kim 2022 (Korea) |

To identify depressed moods and associated factors, and to explore caregiver understanding of delirium |

Survey |

General Hospital Wards |

FC: 224, 44-65, 81% |

56% of caregivers scored 8 or more on the HADS-D. |

| Lloyd 2015 (USA) |

To characterise acute stress symptoms and depression in caregivers witnessing delirium in the general hospital setting |

Observations, survey |

General Hospital Wards |

FC: 40, M=50, 77% |

Family carers who rated witnessing delirium as having a negative impact on their lives had higher scores on impact of events scale. |

| Breier 2018 (USA) |

Evaluated psychometric properties of items assessing delirium risk factors related to cognitive problems, psychological distress and sleep |

Survey |

Hospice |

P: 817, M=80, 47% |

Distress scale of the BDS was most highly correlated with delirium; distress and sleep problems had low correlations with dementia. |

| Head 2005 (USA) |

Capture perceptions of hospice clinicians related to ‘terminal restlessness’ |

Survey |

Hospice |

C: 130 (52% nurses; 26% social workers; 14% chaplains; 8% physicians), M=45, 84% |

Distress, agitation and anxiety were perceived as most common components of terminal restlessness. Behavioural components identified related to the patient’s emotional or mental state, sleeplessness or restlessness, or verbalisations. |

| Haji Assa 2024 (USA) |

Examine the relationship between uncertainty and psychological distress among family caregivers of patients with delirium in ICU |

Survey |

Intensive Care |

P: 120, M=63.4, 54%

FC: 121, M=38, 50% |

No associations found between family characteristics and uncertainty or distress. As level of uncertainty increased, so did distress. |

| Martins 2018 (Portugal) |

Analyse level of distress caused by delirium in patient’s family and their nurses, and to identify factors associated with distress |

Record review, structured interview |

Intensive Care |

P: 42, M=80, 50%

FC: 32, M=51, 81% |

28% of patients developed delirium during the study period. 66.7% of family carers reported severe distress. Family carer distress related to excess drowsiness, psychomotor agitation and disorganised speech. 41.7% of nurses reported severe distress. Nurse distress was related to psychomotor agitation, inattention and disorientation. |

| Miyamoto 2021(Japan) |

Determine associations between delirium and comas during ICU stay and long-term psychiatric symptoms and disability affecting ADL |

Observational |

Intensive Care |

P: 47, 61-81, 41% |

Patients with delirium had more psychiatric symptoms or disabilities affecting ADL at 3 and 12 months than the no delirium group. Those with a longer episode of delirium also had more psychiatric symptoms at 3 and 12 months. Those who had an episode of delirium had a higher risk of PTSD and anxiety symptoms at 12 months than those who did not have an episode. |

| Moura 2022 (Portugal) |

Identify the proportion of patients who recall delirium and analyse distress caused by it |

Survey |

Intensive Care |

P: 105, 65-103, 63% |

Of the 34 patients who completed the DEQ, 53.3% remembered being confused, of which, 9 patients 75% reported to be a distressing experience. Of the 9 patients, 44.4% said that it was a very distressing experience. |

| Poulin 2021 (Canada) |

Examine the association of patient’s delirium in the ICU with patterns of anxiety symptoms in family caregivers |

Survey |

Intensive Care |

FC: 147, M=56, 74% |

Family caregivers of patients with delirium scored significantly higher on “worrying too much about different things” than family caregivers of those without delirium. (CAM-ICU, Odds Ratio [OR] 2.27 [95%CI 1.04–4.91]) |

| Svenningsen 2015 (Denmark) |

Assess the correlation between ICU delirium and the prevalence of PTSD symptoms, other anxiety and depressive symptoms at 2- and 6-months post ICU discharge |

Surveys |

Intensive Care |

P: 299, M=62, 44% |

No association between delirium and PTSD symptoms, anxiety or depression. |

| Wang 2022 (China) |

Investigate the psychological stress of ICU nurses caring for patients with delirium and potential factors |

Survey |

Intensive Care |

C: 355, 70% aged 26-35, 86% |

ICU nurses suffered moderate psychological stress in caring for patients with delirium. Familiarity with delirium knowledge, support provided by department, psychological resilience and occupational coping self-efficacy were significantly inversely related with psychological stress. |

| Racine 2019 (USA) |

Develop separate patient and family caregiver delirium burden instruments to test their content and construct validity |

Expert review, pilot test of measure |

Medical/ Surgical Wards |

P: 247, 80, 57%

FC: 213, N/R, N/R |

Higher delirium severity associated with higher DEL-B scores for both patients and family caregivers. |

| Boland 2022 (UK) |

Determine current clinical practice of specialist palliative medicine physicians regarding their approach to delirium |

Survey |

Palliative Care |

C: 332, N/R, N/R |

48% reported rarely prescribing deep sedation of inpatients in the last days/weeks of life for non-reversable delirium. Perspectives on sedation included that it was hard to distinguish between alleviating distress and providing palliative sedation. |

| De la Cruz 2017 (USA) |

Determine the effect of delirium on the reporting of symptom severity in patients with advanced cancer |

Record review |

Palliative Care |

P: 329, M=57, 55% |

29% of patients developed delirium during admission. Patients with delirium had worse ESAS scores for depression, anxiety, appetite, wellbeing and sleep. |

| Morita 2007 (Japan) |

Explore associations between distress and delirium in bereaved carers |

Surveys |

Palliative Care |

FC: 242, M=69, 87% |

32% of bereaved family carers reported very high distress. More than half of the respondents felt guilt, self-blame and worry and about staying with the patient. One fourth to one third reported feeling a burden over proxy judgement, acceptance and helplessness. Family carers with higher distress were more likely to report patient agitation, incoherent speech, and patient being distressed by noticing they were talking strangely. |

| Kowalska 2020 (Poland) |

Explore the association between in-hospital delirium and depression, anxiety, anger, and apathy after stroke |

Longitudinal survey |

Surgical Ward |

P: 70, N/R, N/R |

Delirium was an independent risk factor for depression and aggression during hospitalisation, anxiety after 3 months, and apathy at all follow up periods. |

| Partridge 2019 (UK) |

Describe distress related to post operative delirium in older surgical patients and their relatives |

Structured clinical assessments, questionaries |

Surgical Ward |

P: 102, M=79, 32%

FC: 49, N/R, N/R |

Distress was significantly higher for those who recalled delirium compared to those who didn’t. No difference in distress scores for those who were given pre-operative information on risk of delirium and those who didn’t.

Family carer distress increased significantly with duration of delirium and severity of delirium. |

| Sorensen 2007 (Sweden) |

Delineate behavioural changes before and during the prodromal phase of delirium |

Observations |

Surgical Wards |

P: 103, 88, 72% |

Behavioural changes were prevalent before delirium onset. These include anxiety, disorientation and decreased psychomotor activity. |

Table 1b.Characteristics of included studies (Qualitative, N=29 as 27 studies)

| First author, date (country) |

Aim |

Methods |

Setting |

Population: N, age, % women |

Results |

| Rose 2021b (UK) |

Gain consensus on measurement methods for outcomes of the COS |

Consensus meetings |

Acute Care |

18 participants, N/R, N/R |

Consensus was reached to use the HADS to measure anxiety and depression symptoms (71%). Emotional distress should be measured up to 12 months but no consensus on measurement intervals. |

| Schmitt 2019 (USA) |

Describe common delirium burdens from the perspective of patients, family caregivers and nurses |

Semi-structured interviews |

Acute Care |

P: 18, M=70, 56%

FC: 16, M=57, 63%

C: 15, M=32, 100% |

Themes: Symptom burden (disorientation, hallucinations/delusions, impaired communication, memory problems, personality changes, sleep disturbances); emotional burden (anger/frustration, emotional distress, fear, guilt, helplessness); situational burden (loss of control, lack of attention, lack of knowledge, lack of resources, safety concerns, unpredictability, unpreparedness) |

| Teodorczuk 2013 (UK) |

Exploring learning needs of hospital staff relating to care needs of the confused older patients |

Interviews and focus groups |

Acute Care |

P: 2, N/R, N/R

FC: 15, N/R, N/R

C: 10, N/R, N/R |

Identified learning needs: ownership of the patient; attitudes; awareness of how frightening the hospital setting is; recognition of cognitive impairment; person-centred care; family carer partnership; communication; specific clinical learning needs |

| Bruera 2009 (USA) |

Determine frequency of recall and the associated level of distress for primary family carer |

Interviews |

Cancer |

P & FC: 99 dyads, M=55, 72% |

Median distress for patients was higher when they were able to recall delirium versus not able to recall. High agreement on which delirium symptoms were distressing between patients and family carers. |

| Cohen 2009 (USA) |

To better understand delirium-related distress |

Interviews |

Cancer |

P: 34, M=63, 53%

FC: 37, M=56, 76% |

Themes: vivid memories of distressing experience, cause of the confusion, concerns about the future |

| Greaves 2008 (AUS) |

Understanding delirium from the Australian caregiver’s perspective |

Semi-structured interviews |

Cancer |

FC: 10, 51-69, 60% |

Themes: features of the delirium (aggression, withdrawal, changes in perception, symptoms worse in family carer’s presence); caregiver response to the delirium (treatment related delirium, not the same person, inability to communicate or say goodbye, fear, burden of physical caring, feelings of isolation, embarrassment); caregiver meaning to the delirium (regret, decision making burden, not meeting patient’s needs, guilt, bereavement issues) |

| Lingehall 2015 (Sweden) |

Illuminate experiences of undergoing cardiac surgery in older people diagnosed with postoperative delirium |

Interviews |

General Hospital Ward |

P: 47, M=78, 35% |

Themes: feeling drained of viability (having a body under attach; losing strength; being close to death); feeling trapped in a weird world (hallucinating; being in a nightmare; being remorseful); being met with disrespect (feeling disappointed; being forced; feeling like cargo); feeling safe (being in supportive hands, feeling grateful) |

| Schofield 1997 (UK) |

Explore patients’ perceptions of an episode of delirium |

Cross-sectional semi-structured interviews |

General Hospital Ward |

P: 19, 66-91, N/R |

Themes: the nature/quality of the experience (unpleasant memories, wholly unpleasant, feelings of detachment); reactions to the experience (caution, explanations to relatives, memory loss, reluctance to discuss); explaining the experience; aftereffects (dismissing) |

| Uchida 2018 (Japan) |

Explore the views of health care professionals regarding care and treatment goals in irreversible terminal delirium and their effect on patients and caregivers |

Semi-structured interviews |

General Hospital Wards |

C: 21, M=40, 52% |

Themes: adequate management of symptoms/distress; ability to communicate; continuity of self; provision of care and support to families; considering a balance |

| Featherstone 2023 (UK) |

To explore hospice staff and volunteers practice, it’s influence and what may need to change to improve hospice care |

Interview |

Hospice |

C: 37, 21-73, 92% |

Themes: emotional responses to delirium are powerful drivers of care; Varied understanding of delirium influences the reactive focus on managing hyperactive symptoms; hospice culture and environment influence person-centred delirium care |

| Namba 2007 (Japan) |

Explore bereaved family carers experiences of delirium |

Interviews |

Hospice |

FC: 20, 42-75, 55% |

Themes: experience of delirium; emotion (positive or neutral, distress, guilt, anxiety and worry, difficulty in coping, helplessness and exhaustion, burden to others, ambivalence); perception of delirium; recommended supports. |

| Bohart 2018 (Denmark) |

To explore relatives’ experiences of delirium in the critically ill patient admitted to ICU |

Interviews |

Intensive Care |

FC: 11, 51-76, 73% |

Themes: delirium is not the main concern; communication with health care professionals is crucial; delirium impacts on relatives |

| Clarke 2022 (UK) |

To generate knowledge on experiences of psychological and physical rehabilitation |

Interviews |

Intensive Care |

P: 20, 15-79, 55% |

Themes: sense making difficulties; rehabilitation context; making sense of self. Participants were not directly asked about delirium but many shared experiences |

| Granberg 1999 (Sweden) |

Describe and illuminate patients’ experience of acute confusion during and after ICU stay |

semi-structured interviews |

Intensive Care |

P: 19, 25-82, 32% |

Themes: perceptions of time and day; being afraid of falling asleep; thought, speech, language and communication; patients’ descriptions of unreal experiences; the variety and extent of unreal experiences; experiences after discharge from ICU |

| Huang 2022 (Tiwan) |

To understand the experiences of family caregivers with a family member as a patient with delirium in the ICU in Taiwan |

Interviews |

Intensive Care |

FC: 20, M=52, 55% |

Themes: perplexity of the ICU environment, perplexity of making decisions, perplexity of Chinese cultural constraints. |

| Lange 2022 (Poland) |

Explore patient and family experiences of delirium |

Interviews |

Intensive Care |

P: 8, 61-80, 25%

FC: 8, N/R, N/R |

Themes: education, feelings before the delirium, pain and thirst, the day after, talking to the family/patient, returning home |

| Mortensen 2023 (Denmark) |

To explore experiences of critically ill patients with delirium during the ICU stay, from ICU discharge until 1 year follow up |

Interviews |

Intensive Care |

P:17, M=69, 53% |

Themes: from enduring to adapting; struggling to regain a functional life; struggling to regain normal cognition; distressing manifestations from the ICU |

| Pandhal 2022 (UK) |

To explore perceptions of patients and their families together, regarding the involvement of family in delirium management |

Interviews |

Intensive Care |

P: 9, 49-88, N/R

FC: 9, N/R, N/R |

Themes: understanding and education about delirium, influencers of delirium management, and family-based delirium care. |

| Rose 2021a (UK) |

Develop consensus among key stakeholders for a core outcome set (COS) for future trials of interventions to prevent and/or treat delirium |

Modified Delphi method (surveys and interviews) |

Intensive Care |

P: 18, N/R, N/R

Delphi: 110 participants |

Emotional distress (fear and anxiety related to delirium symptoms such a delusions) and delirium severity were identified by over 50% of interview participants. The final outcomes selected for the COS are delirium occurrence and recurrence; delirium severity; delirium duration; cognition; emotional distress; health related quality of life |

| Teece 2022 (UK) |

Explore the decision-making process of critical care nurses when considering restraint for a patient with hyperactive delirium |

Interviews |

Intensive Care |

C: 30, N/R, N/R |

Themes: intrinsic beliefs and aptitudes; handover and labelling and influence decision making; failure to maintain a consistent approach; restraint might be used to replace vigilance; the tyranny of the now |

| Whitehorne 2015 (Canada) |

What is the lived experience of the ICU for patients who have experienced delirium |

Interviews |

Intensive Care |

P: 10, 46-70, 30% |

Themes: I can’t remember; wanting to make a connection, trying to get it straight, fear and safety concerns |

| Yue 2015 (China) |

Explore experience of nurses caring for patients with delirium in ICU in China |

Interviews |

Intensive Care |

C: 14, N/R, N/R |

Themes: internal and external barriers to care; care burden: workload, psychological pressure and injury; dilemmas in decision making balancing risks and benefits |

| Julian 2022 (Canada) |

To explore experiences of family caregivers providing support to older persons with delirium superimposed on dementia |

Interviews |

Medical Wards |

FC: 9, 50-80, 89% |

Themes: an overwhelming experience; lacked information; distress, helplessness, shock and sadness |

| Pollard 2015 (AUS) |

Explore and recount the experience older people had of being delirious following orthopaedic surgery |

Semi-structured interviews |

Orthopaedic ward |

P: 11, 54-87, 27% |

Themes: Living the delirium (the feeling, suspicion and mistrust, being trapped, to be abandoned, the dismissal, the disconnection); Living after the delirium (the strength, why was this happening to me? the shame and guilt, the remaining scars, the strength of healing) |

| Brajtman 2005 (Canada) |

Explore an interdisciplinary team’s perceptions of family’s needs and experiences regarding terminal restlessness |

Focus Groups |

Palliative Care |

C: 12 (4 nurses, 1 physician, 1 social worker in each group), N/R, N/R |

Themes: suffering; maintaining control; feelings of ambivalence regarding sedation; valuing communication to reduce conflict |

| Hosie 2014 (AUS) |

To explore the experiences, views and practices of inpatient palliative care nurses in delirium recognition and assessment |

Interviews |

Palliative Care |

C: 30, N/R, 96% |

Themes: The delirium experience (Patients’ delirium: causes, presentations and outcomes, Concern for the patient and self); Nursing knowledge and practice in delirium recognition and assessment (Challenges framing and naming observed changes, Varying comprehensiveness of assessment, Inter-personal relationships and communication are valued, Uncertainty and challenges promote desire for learning) |

| Brajtman 2006 (Canada) |

Exploring palliative care unit and home care nurses’ experiences of caring for patients with terminal delirium |

Semi-structured interviews |

Palliative Care / Palliative Home Care |

C: 9, N/R, N/R |

Themes: experiencing distress; the importance of presence; valuing the team; the need to know more |

| Agar 2012 (AUS) |

Explore nurse’s assessment and management of delirium when caring for people with cancer, the elderly or older people requiring psychiatric inpatient care |

Semi-structured interviews |

Palliative Care, Aged Care, Geriatric Psychiatry and Oncology |

C: 40, M=45, N/R |

Themes: superficial recognition and understanding of delirium as a syndrome; nursing assessment: investigative versus a problem-solving approach; management: maintaining dignity and minimizing chaos; distress and the effect on others |

| Meilak 2020 (UK) |

To understand the views of patients and relatives regarding: the content of an intervention to be delivered, the timing and who should deliver it |

Semi-structured interviews |

Surgical Wards |

P: 11, 66-81, 36%

FC: 12, 47-74, 50% |

Themes: prior knowledge of delirium; impact of delirium; own attribution to cause of delirium; communication; timing of communication; format of information; environmental considerations; suggested areas for improvement |

Table 1c.Characteristics of included studies (Mixed methods, N=7)

| First author, date (country) |

Aim |

Methods |

Setting |

Population: N, age, % women |

Results |

| Hui 2021 (USA) |

Determine pattern of neuroleptic dose and the relationship between neuroleptic dose with recall and distress |

Retrospective record review, assessments, interview |

Cancer |

P: 99 M=60, 46%

FC: 99, M=55, 73% |

Neither haloperidol dose or haloperidol equivalent daily dose (HEDD) varied according to patients recall or distress level. Haloperidol dose increased significantly with nurses recall and distress related to patient delusions and agitation. Nurses’ own distress was also a significant predictor of haloperidol dose or HEDD. |

| Grover 2011 (India) |

Explore patient’s experiences of delirium in terms of recollection and distress |

Survey/ Interviews |

General Hospital |

P: 53, M=46, 29% |

Those who could recall delirium had severe (40%) or very severe (33.3%) distress. General themes for qualitative component (question 6 of DEQ) were fearfulness, anxiety, confusion and feeling strange |

| Toye 2014 (AUS) |

Describe families experience, understanding of delirium and delirium care and support needs |

Survey and interviews |

General Hospital Ward |

FC: 17, M=91. 82% |

From the survey: worry about future care and seeing patient affected by delirium distressing were most highly rated

Themes from interviews: the admission experience; worries and concerns; feeling supported; the discharge experience |

| Kerr 2013 (USA) |

Describe caregiver observations regarding onset, characteristics and progression of the pre-delirium state in hospice patients diagnosed with delirium |

Interviews, multi-dimensional scaling |

Hospice |

P: 20, N/R, N/R

FC: 20, N/R, N/R

C: 10, N/R, N/R (all doctors) |

Reported clusters of symptoms: agitation/restlessness; night-time anxiety; sleep disturbance; daytime sleep pattern; gradual cognitive decline; confusion; perceptual disturbance; psychological distress; physical distress; family caregiver distress. |

| Rose 2023 (UK) |

To develop international consensus among key stakeholders for a core outcome set for future trials of interventions to prevent and/or treat delirium in critically ill adults. |

Interviews, surveys, face-to-face consensus meeting |

Intensive Care |

P: 12, N/R, N/R

FC: 12, N/R, N/R |

Final outcomes set to prevent and/or treat delirium in ICU are delirium occurrence; cognition including memory; mortality; emotional distress including anxiety, depression, acute stress and posttraumatic stress disorder; delirium severity; health related quality of life; time to delirium resolution. |

| Bryans 2024 (UK) |

To undertake an international consensus process to develop a core outcome set for trials of interventions for delirium in palliative care |

Review, Interviews, Delphi |

Palliative Care |

C/FC: 16, N/A, N/A |

Level of distress to patient, and level of distress to family were both identified by 63% of interview participants. From the Delphi process, patient distress was rated as 97% critical. Distress due to delirium (patient, family member, carer) is included in the final core outcome set. |

| Morandi 2015 (Italy) |

Assess the delirium superimposed on dementia experience among older patients |

Surveys and interview |

Rehabilitation Ward |

P: 30, M=83, “mostly women” |

In patients who remembered the delirium, the most frequently remembered symptoms were deficits in sustained and shifting attention, orientation, consciousness, apathy and restlessness.

Distress was largely maintained at baseline and 1-month follow up. Themes from interviews: anxiety, fear, anger, threat and shame; confusion, difficulties in comprehension, disorientation, and altered perception of time; feeling confined, disturbing and rambling thoughts, delusions, depersonalisation, nightmares and hallucinations; memories, awareness of change; being restrained, falls, constraints and drowsiness |

Legend: P = patient, FC = family carer, C = clinician, M = mean, BDS = Buffalo Delirium Scale, ESAS = The Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale, HADS-D = Depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, ADL = activities of daily living, PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; DEQ = delirium experience questionnaire, DEL-B = delirium burden questionnaire, ICU = intensive care unit

Twenty-one studies were conducted in general hospital wards13,26,29,30,33,37,40,43,45–47,51,52,56,61,63,64,72,74,77; 18 in Intensive Care Units (ICU) or with ICU survivors12,13,27,38,42,44,53,57,58,62,65,67–71,73,75; 18 in palliative care and hospice units14,22,25,28,31,32,34–36,39,48–50,54,55,59–61; four in oncology24,35,48,61; two in geriatric wards48,50; two in psychiatry23,48; and one in a specialised delirium unit.52

Overall, there were 6388 participants: 2991 patients (mean age 70 years), 1808 family carers (mean age 58 years), and 1589 hospital staff (mean age 43 years: 72% nurses). Of the studies that reported patients’ primary condition or treatment focus, these included cancer,23–25,31,32,34,35,49,59,61 cardiac surgery,63 stroke,72 COVID-1926 and dementia.56

Of the twenty-three quantitative papers, six compared the outcomes of patients who did and did not develop delirium: three in intensive care unit settings,53,58,71 two in palliative care or hospice,22,25 and one in a general hospital ward.26

Key findings on antecedents, attributes, consequences and protective factors of delirium-related distress are described below, and summarised in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Table 2.Concept Analysis findings

| Citation |

Antecedents |

Attributes |

Consequences |

Protective factors |

| Pollard 2015 |

Vivid memories |

Horror, terror, fear, terrifying, horrendous, frightening, shocking, dreadful, daunting, felt like dying, threatening. Some spoke as if hallucinations were real. Loneliness, abandonment, felt powerless over the level of care and support (P) |

Shame, guilt, going mad, patients keen to tell interviewer that how they acted when delirious is not the ‘real them’, health avoidance (didn’t go to GP in case they were sent back to hospital) (P) |

Patients felt unsafe, but feelings of security returned if their loved ones were present. Felt relieved to be discharged to safety of own home. (P) |

| Brajtman 2006 |

Nurses thought delirium was an expression of existential distress |

Nurses felt emotionally challenged and disturbed. (C) |

Nurses wanted to control the distressing symptoms so that family wouldn’t be left with ‘disturbing memories’ (C) |

Presence of another person

Therapeutic touch

Continuity of care (C) |

| Lange 2022 |

Most patients didn’t know that delirium could result from surgery |

Patients remembered hallucinations that caused fear and anger. (P) |

Felt that knowledge about delirium could have reduced their anxiety (P; FC) |

Most patients found family and nurses supportive after delirium (P) |

| Agar 2012 |

Time pressure, budget restrictions, staffing mixes, high care acuity |

Distressing and exhausting (C) |

Impeded a good death in palliative care and oncology (C) |

|

| Meilak 2020 |

Less information about delirium = more distress(P; FC) |

Patients said that they worried the delirium had a negative impact on their family. (P)

Relatives found it distressing to not be recognised by the patient, and to witness irrational or paranoid behaviour. |

One patient said that it was so distressing for her friend that her friend stopped visiting for a while. Families wanted information and emotional support. Patients’ health anxiety increased; one said that they will be careful what medicine they take before bed. (P) |

|

| Hosie 2014 |

Gaps in knowledge |

Paranoia, anger, agitation, fear (P) |

Patients concerned about their behaviour following delirium. (P) |

|

| Julian 2022 |

Family carers were emotionally unprepared for challenging behaviours. Difficulty accessing information about delirium superimposed on dementia (FC) |

Family caregivers felt alarmed when witnessing behaviours; felt helpless when they couldn’t alleviate the situation; a lack of information contributed to their distress. (FC) |

|

Family carers were able to assist patients in cooperating with nurses as they were a familiar presence. Family carers who were acknowledged as part of the care team felt lower levels of stress than those who weren’t. (FC) |

| Morandi 2015 |

Those who remembered delirium had shorter duration, higher severity and remembered problems with shifting attention and apathy |

Anxiety was recalled more at one-month interview than baseline. Distress at baseline was mostly related to fear/anxiety and restlessness. (P) |

|

|

| Head 2005 |

Staff felt emotional distress was a symptom of terminal restlessness. |

Causes thought to be psychosocial or spiritual. (C) |

|

|

| Brajtman 2005 |

Lack of time or nurse manpower can result in med use |

Staff felt torn between need of patient to be sedated and need of family to communicate with patient. (C) |

|

|

| Bohart 2018 |

|

Worries, questioning, is it dangerous, family distressed when patient couldn’t recognise them (FC) |

Relatives cautious of what they said to patient as they didn’t want to increase their anxiety, relatives uncertain about the future. (FC) |

Relatives felt relieved when they received information about delirium. (FC) |

| Featherstone 2023 |

|

Doctors and nurses were distressed when unable to resolve delirium or comfort patient at end of life. (C) |

Emotional and hospital culture pressures motivated clinical staff to seek and immediate way to control hypoactive symptoms. (C) |

Family can be useful for calming patients, but nurses recognised that this can be stressful for the family. (C) |

| Schofield 1997 |

|

Hallucinations could be distressing if loved ones present in hallucination that they could not interact with. (P) |

Actively trying to forget memory

Denying

Dismissing episode once it has passed (P) |

Patients remembered nurses attempts to reorient them. (P) |

| Kerr 2013 |

|

Symptoms that resulted in quicker hospital admission were psychological distress, agitation and restlessness, perceptual disturbances and cognition. (P) |

Fear of sleeping because of dreams, not recognising faces, curiosity/worry about the dying process (P) |

|

| Toye 2014 |

|

Shock, sadness, stress, anxiety. Distressing to see patient delirious. (FC) |

Concerns about future care (FC) |

|

| Schmitt 2019 |

|

Disorientation to time, seeing things (P)

Not knowing if symptoms would go away (FC)

Unable to properly care because unable to manage hallucinations

Disorientation and hallucinations distressing for all three groups. (C) |

Hospital avoidance (one patient cancelled two appointments because they were afraid delirium would return.). (P) |

|

| Partridge 2019 |

|

Perceptual disturbances, delusions and lability of affect associated with patient distress. (P)

Family carer distress increased with delirium duration. (FC) |

Correlation at 6 and 12 months between family carer distress and mean DRS score (FC) |

|

| Lingehall 2015 |

|

Patients found the change in their behaviour to be unpleasant, bothering and embarrassing.

Frustration, anger, fear, anxiety, loneliness, ‘horror filled experience’ (P) |

Felt the need to apologise for their behaviour.

Some afraid and ashamed

Kept the delirium a secret and didn’t ask for an explanation (P) |

|

| Cohen 2009 |

|

Patients and family found hallucinations distressing. Family found it frightening to not know the cause (P; FC) |

Caregivers had concerns for the patient’s future health and their own future health (FC) |

|

| Breitbart 2002 |

|

perceptual disturbances, delusions, higher KPS scores (P)

brain metastases, hyperactive subtype

delirium severity, perceptual disturbances (FC) |

Of those who recalled delirium 80% of patients, 76% of spouses, and 73% of nurses reported severe distress (P; FC; C) |

|

| Teece 2022 |

|

Nurses recognise that judging agitation is subjective and can feel less confident in their decisions if doctors have different preferences for treating delirium. Nursing a patient with delirium can be emotionally and physically exhausting (C) |

Therapeutic engagement decreases as nurses’ loose patients and get more tired. Nurses feel that doctors don’t appreciate their experience of patient distress. (C) |

|

| Svenningsen 2015 |

|

Memories of delusions were significant for patients with anxiety at two months, delirium did not affect QoL scores (P) |

No association found between delirium and PTSD, depression, or anxiety (P) |

|

| Namba 2007 |

|

Guilt; anxiety and worry; difficulty coping; exhaustion; burden on others (FC) |

Not wanting children to see person in active delirium; felt they caused the delirium; wanted patient to stay awake but also to sleep or die in peace (FC) |

|

| Martins 2018 |

|

Drowsiness, psychomotor agitation and disorganised speech. (FC) Agitation, inattention and disorientation (C) |

Younger family members more distressed, half of nurses’ thought delirium was distressing for the patient, but this wasn’t related to their own distress. (FC) |

|

| Teodorczuk 2013 |

|

Family carers thought staff treated patient as if they are mad. (FC) |

Personhood ignored for patient (FC) |

|

| Rose 2021 a&b, Rose 2023 |

|

Emotional distress, delirium severity and getting back to pre-delirium cognitive level were most important for survivors and family. (P; FC) |

Emotional wellbeing rated as 100% critical by family and patients. Emotional distress and HRQoL included in core outcome set. HADS reached consensus for measuring anxiety and depression. Emotional distress should be measured up to 12 months at various intervals, but the time frames were not agreed on. Understanding baseline emotional distress was important. (P; FC; C) |

|

| Kowalska 2020 |

|

During hospital stay and at 3 months, delirium is an independent risk factor for depression, anxiety and hostility. (P) |

Anxiety and depression slightly reduced at 12 months; apathy did not. (P) |

|

| Breier 2018 |

|

Distress factor includes personality change, hallucinations and restlessness/agitation. (P) |

Distress scale had highest correlation with delirium (r=.40). (P) |

|

| Clarke 2022 |

|

Confusing, difficult to distinguish from reality, feeling anxious and ‘jumpy’ (P) |

One patient had graphic memories in their sleep for weeks after discharge. (P) |

|

| Greaves 2008 |

|

Aggressive patients made family carers more distressed; feeling as though they had ‘lost’ the person; feeling embarrassed (FC) |

Sedation of patient for their anxiety meant that family couldn’t say goodbye; some felt that they could have cared better for the person who died. (FC) |

|

| Yue 2015 |

|

Afraid of hypoactive delirium because it’s hard to recognise, increased psychological pressure, moral stress.

Nervous, worried, afraid, exhausted under pressure (C) |

|

Bringing in families helps comfort the patients. (C) |

| Racine 2019 |

|

Testing of scale. ‘Afraid of losing their mind’ rated in top 5 items by 75% of panel. ‘Feelings of helplessness as a caregiver’ also in top 5 by 75% of panel. |

|

|

| Bruera 2009 |

|

81% said delirium was distressing

Distress related to psychomotor agitation, delusions and orientation to time. (P) |

|

|

| Grover 2011 |

|

Of those who recalled delirium, 73% had severe or very severe distress, related to fear, confusion, and anxiety. (P) |

|

|

| Wang 2022 |

|

Nurses experienced moderate psychological stress in caring for patients with delirium. Familiarity with delirium knowledge, satisfaction with department support, resilience and self-efficacy all associated with psychological stress (C) |

|

|

| Uchida 2018 |

|

Important for psychiatric symptoms of delirium to be controlled, important for patients to feel at peace and secure, important to maintain continuity of self (P) |

|

|

| Kim 2022 |

|

Higher caregiver depression associated with patient history of depression, delirium severity, caregiver misinterpretation of delirium as dementia (FC) |

|

|

| Moura 2022 |

|

Half of the patients who remembered delirium and were distressed said it was ‘extremely distressing.’ (P) |

|

|

| Buss 2007 |

|

12x more likely to have symptoms of anxiety, related to patient pain, dehydration, falls and thinking the patient was dead. (FC) |

|

|

| Lloyd 2015 |

|

Family carers who had traumatic stress reaction were more likely to have a history of depression or to have rated witnessing delirium as having a negative impact on their life. (FC) |

|

|

| Hui 2021 |

|

Family carers and nurses preferred the patient to be at a deeper level of sedation. Nurses more likely than family to prefer deeper level of sedation. (FC: C) |

|

|

| Huang 2022 |

|

Families feared that delirium meant the patient was dying, likened physical restraints and tubes to being tied up like a prisoner. (FC) |

|

|

| Hull 2010 |

|

Amount of haloperidol given did not impact recall or distress for patient. Higher distress in nurses resulted in higher daily dose. (C) |

|

|

| Morita 2007 |

|

Ambivalence; guilt and self-blame; worry; burden to others; helplessness (P) |

|

|

| Whitehorne 2015 |

|

Lack of memory of experience was distressing for some; frustration and fear at not being able to communicate (P) |

|

|

| Granberg 1999 |

|

Afraid of falling asleep; fear of becoming ‘crazy’; frustration at not being able to communicate; feelings of ‘emptiness’ after sedation; terrifying nightmares; feeling emotionally vulnerable (P) |

|

|

| Hosie 2021 |

|

78% of respondents said that the goal of using an antipsychotic was to reduce patient distress, 67% said it was to reduce unwanted behaviours. (C) |

|

|

| Poulin 2021 |

|

34% of family carers had clinically significant anxiety symptoms, 20% reported severe anxiety. (FC) |

|

|

| Pandhal 2022 |

|

|

Many didn’t receive info about delirium during hospital stay, only at follow up appointment. (P) |

Talking to staff was helpful for patients if the staff did not feature in their hallucinations. Family presence helped patients feel more positive emotions. (P) |

| Miyamoto 2021 |

|

|

Those who had delirium had more psychiatric symptoms or disabilities effecting ADL at 3 and 12 months. Patients with delirium had higher risk of PTSD and anxiety symptoms at the same time points (P) |

|

| De la Cruz 2017 |

|

|

Patients with delirium had worse scores for depression, anxiety, appetite, wellbeing and sleep. (P) |

|

| Haji Assa 2024 |

|

|

Family carers reported moderate to severe psychological distress, and substantial uncertainty around the delirium. There was a positive correlation between distress and uncertainty. (FC) |

|

| Bryans 2023 |

|

|

Emotional distress was identified as a core outcome by 63% of interview participants. Emotional distress was rated as 100% critical by clinicians. Distress due to delirium for patients, family members and carers was included in the final core outcome set. (P; FC; C) |

|

| Mortensen 2023 |

|

|

Distressing memories, frustration around decline in functional capacity, fear of ‘losing words’ in social interactions due to cognitive impairments. 12 months later, participants sometimes still did not want to talk about distressing memories of the ICU. Memories of hallucinations remained vivid and intense. (P) |

|

| Han 2023 |

|

|

Delirium during ICU was related to higher 12-month PTSD symptom severity and worsening delirium symptom severity. There was no association between delirium and 12-month global cognition scores. (P) |

|

| Aggar 2024 |

|

|

Carer burden and distress did not change significantly post-intervention. (FC) |

|

| Boland 2022 |

|

|

91% of clinicians would prescribe an antipsychotic for hallucinations that aren’t responsive to non-pharmacological strategies. (C) |

|

Legend: P = patient, FC = family carer, C = clinician

Figure 2.Synthesised findings of the concept analysis

Legend: P = patient, FC = family carer, C = clinician

Antecedents

Patients identified a lack of prior knowledge about delirium40,73,76; and vivid memories or recall of delirium51 as factors impacting their distress. Carers reported that feeling unprepared for challenging behaviours associated with delirium influenced their own distress.56 Hospital staff identified lack of time48,54; poor understanding of delirium50; high care acuity and inadequate patient-to-staff ratios48 as antecedents.

Attributes

Attributes mainly reflected psycho-emotional outcomes during delirium. Fear was experienced by up to 73% of patients during delirium-related distress,74 and was caused by graphic dreams, hallucinations, and nightmares32,34,38,43,47,63,73,74; agitation and restlessness31,71; and limited information on delirium.63 Similarly, up to 34% of carers reported fear,24,53 and worry about caring for the patient.56,59

Patients described a depressed mood as feelings of loneliness or disconnection51,57,63; powerlessness33,51,57; or depersonalisation.64,76 Carers described depressed mood related to an inability of the patient to recognise them,40,66 feeling like a burden on the patient and others,59 or the experience of witnessing the delirium.32,52

Anxiety for patients was feeling ‘curious and worried’ about the dying process,34 or concern for the effects of delirium on their families.40 For carers, anxiety was related to worry that the delirium was dangerous for the patient.66

Stress during an episode of delirium-related distress was identified by up to 50% of carers,29 related to younger age of the carer,71 delirium duration and severity.37 Carers with higher levels of stress preferred deeper levels of sedation for the patient.35 Hospital staff felt stressed when they could not relieve delirium symptoms or perceived the patient to be uncomfortable,39,54,55,61 this stress decreased with higher delirium knowledge.68 An Australian study found 78% of clinicians (nurses, physicians and pharmacists) gave antipsychotics to patients with delirium with the intent of reducing distress.47 A preference for deeper sedation was related to palliative care nurses’ own delirium-related distress.35 Antipsychotics and benzodiazepine use increased nurse’s delirium-related distress if it did not effectively reduce patient distress.39 Nurses in Australia also reported feelings of ambivalence around antipsychotic and benzodiazepine use; feeling the need to over-sedate to minimise family anxiety from witnessing patient’s distressing symptoms, which opposed providing person-centred care and a ‘good death.’48

Frustration was common for patients with delirium who perceived they could not communicate with the people during their hallucinations.43,64

Consequences

Psycho-emotional outcomes were also reported after delirium. Patients showed depressed mood and lower wellbeing and sleep scores compared to patients who did not develop delirium.25 Delirium was an independent risk factor for depression and anxiety after three months,65,72 PTSD symptoms after twelve months,26 and psychiatric symptoms effecting daily life.58

Patients reported feeling fear after delirium.34,63,67 Patients also reported feeling ashamed,64 and a need to apologise for their behaviour.50,63,64

Anxiety for patients manifested as avoiding falling asleep to prevent re-living hallucinations through dreams,34 avoiding health check-ups for fear they may go back to hospital and experience delirium again,51 caution when taking medication,40 and dismissing the severity of the delirium episode with health professionals and family.43 Carers also reported concern that the patient may have a repeat episode.27,32,52 Carers felt as though they were a burden on the patient,33,52,60,75 or felt that they should have done more, especially in instances when the patient died.49

Frustration was present for patients who experienced decreased function following delirium.67

Regarding longer term psycho-emotional impacts of delirium for patients, a small number of studies examined outcomes at various time points. One survey study in a general hospital ward26 found that delirium was independently associated with worsening 12-month PTSD (aOR = 3.44, 95% CI: 1.89, 6.28) and depression (aOR = 2.18, 95% CI: 1.23, 3.84) symptoms. An observational study in ICU58 found that delirium was an independent risk factor for psychiatric symptoms or disability effecting activities of daily life (ADL) at three months (aOR: 3.38; 1.10-10.38) and twelve months (aOR 8.28; 1.48-46.46). A survey study in ICU65 found no association between delirium and PTSD symptoms, anxiety or depression at two and six months post ICU discharge. Finally, a longitudinal study in a hospital ward involving patients with stroke72 found that delirium was an independent risk factor for anxiety three months post-stroke (OR = 2.83, 95%CI 1.25–6.39, p = 0.012), and for apathy after three (OR = 3.84, 95%CI 1.31–11.21, p = 0.014) and 12 months (OR = 4.95, 95%CI 1.68–14.54, p = 0.004) post-stroke.

Protective Factors.

Feeling safe was a protective factor against delirium-related distress. For example, having family members or friends present who could provide reassurance, increased feelings of safety51,55–57 and comfort.39,69,73 However, while often beneficial to the patient’s emotional wellbeing, family and friends reported witnessing delirium could be stressful.39 Nurses also contributed to patients feeling safer, with some patients reporting memories of kindness from nurses.43

Patients reported that having an opportunity to talk about delirium after an episode was beneficial,57,73 as was reassurance that their hallucinations were not real,57 and when carers and nurses were supportive and empathetic.73 Talking to nurses and other hospital staff however was only helpful for patients if they had not been a feature of their hallucinations.42 Carers also reported receiving emotional support from nurses and other hospital staff would have reduced their distress.66

Empirical Referents

Empirical referents identified by this review were the Delirium Experience Questionnaire,23 Delirium-O-Meter,76 and Delirium Burden Questionnaire.30,46 Levels of distress for patients, family carers and staff were variable,23,31,35,70,71,74,76 and in the three studies that reported the proportion of patients with delirium who experienced no distress, this ranged from none to one quarter of patients.31,70,74 See Table 3 for a summary of these measures.

Table 3.Tools for Measuring Delirium-Related Distress

| Tool |

Key Aspects |

Psychometric Properties |

| Delirium Experience Questionnaire (n=7 studies) |

Do you remember being confused? Yes or No

If no, are you distressed that you can’t remember? Yes or No

How distressed? 0–4, 0 = not at all and 4 = extremely

If you do remember being confused, was the experience distressing? Yes or No

How distressing? 0–4, 0 = not at all and 4 = extremely

Can you describe the experience? (this final question is qualitative) |

Only face validity and content validity reported. |

| Delirium Burden Questionnaire (n=2 studies) |

Items have two levels, the first is Yes/No and the second is rating how distressing the experience was from 0-4 (0=not distressing, 4=very distressing) |

Face, content and discriminant validity reported.

Test-retest reliability reported rho =.73 for family carers, not tested for patients (Racine 2019) |

Patient DEL-B

- Unsure of where they were

- Could not remember parts of the hospital stay

- Saw or heard things that were not there

- Nightmares or vivid dreams that were intense or bothersome

- Suddenly felt confused

- Thought that they would not get better

- Afraid of losing their mind

- Restricted from getting out of a bed or a chair with alarms or restraints

|

Family Caregiver DEL-B

- Loved one did not recognise caregiver

- Loved one experienced change in memory and thinking

- Loved one saw or heard things that were not there

- Loved one became irritable or angry

- Feelings of helplessness as a caregiver

- Concerns about increased responsibilities as a caregiver

- Concern that loved one would never be back to his/her usual self

- Loved one demonstrated unsafe behaviours

|

| Delirium-O-Meter (n=1 study) |

12 item observation scale with each item scored 0-3 (0=absent; no pathology, 1=mild disturbances; 2=moderate, 3=severe)

- Sustained attention

- Shifting of attention

- Orientation

- Consciousness disturbance

- Apathy

|

- Hypokinesia/psychomotor retardation

- Incoherence

- Fluctuating functioning (diurnal variation/sleep-wake cycle)

- Restlessness (psychomotor agitation)

- Delusions

- Hallucinations

- Anxiety/Fear

|

Face and content validity reported. Inter-rater reliability reported. |

A series of studies from the Del-COrS group12–14 aimed to determine a core outcome set (COS) for delirium. Authors identified emotional distress as a core outcome important to survivors of delirium and their families, with emotional wellbeing rated as 97% critical.14 A follow-up consensus study12 confirmed that the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was useful to measure anxiety and depression, but not stress or post-traumatic stress symptoms; and that emotional distress should be measured up to 12 months post-delirium; however, the intervals for measurement were not agreed upon.

Constructed Cases

Four constructed cases are presented in Table 4: a model case highlighting defining attributes of delirium-related distress; a related case which does not include all defining attributes; a borderline case which closely resembles delirium-related distress but is not immediately evident as such; and a contrary case which provides divergent attributes not consistent with delirium-related distress.

Table 4.Constructed Cases

| Constructed Case |

Explanatory notes

|

| Model Case: Dave is an 80-year-old man, currently in hospital recovering from bypass surgery to treat his coronary artery disease. He has no other serious illnesses. Dave’s family have noticed that he has been acting out of character during the last few days. They say Dave is usually a gentle and courteous man, but lately, he has been yelling at the medical team and refusing medications and food. Dave appears to be feeling stressed and frightened. Dave’s wife states she is concerned about what might happen to Dave. |

Dave appears to be feeling stressed and frightened, attributes of delirium-related distress.

Dave’s wife reports concern for him, an attribute and consequence of delirium-related distress. |

| Related Case: Steve is 45 years old and has been admitted to hospital after an altercation with security at his local shopping centre. Steve has told his nurse that he thought the security were FBI agents in disguise and were there to “take me away.” Steve has a prescription for Chlorpromazine but has not had this filled at his local pharmacy. Steve is very vocal and displaying exaggerated and aggressive behaviours. |

Steve is having delusions, which can occur in delirium. Steve has schizophrenia and the cause of his delusions is due to stopping his medication. |

| Borderline Case: Catherine is 75 years old and recovering from hip replacement surgery. She has been assessed for delirium using the 4AT and says that she is experiencing hallucinations. She states that the hallucinations are pleasant as she can communicate with her partner who died many years ago. In addition, Catherine has been sleeping more than usual and said that she can’t remember what the nurses have told her. Catherine has said that while these hallucinations are mostly pleasant, she has noticed that they also made her feel sad and teary. |

Catherine reports that she feels sad and teary because of her hallucinations but has also said they are pleasant.

To ascertain if Catherine is experiencing delirium-related distress, clarifying questions are needed. |

| Contrary Case: Ash is 80 years old and has recently been transferred to a palliative care ward as his needs are too great for his nursing home. Ash has been displaying clear signs of delirium, but states to the nurses that this was not a distressing experience. His hallucinations were of pleasant previous life experiences. Ash can communicate clearly with his family and has good social support. |

Ash has signs of delirium but has stated that he is not distressed by this experience and is not showing any signs of distress. |

Discussion

The objective of this scoping review and concept analysis was to develop a cohesive understanding of delirium-related distress to inform future research. Psychological distress, as defined by the American Psychological Association, is “a set of painful mental and physical symptoms…”.78 The Del-COrS characterised emotional distress as “including anxiety, depression, acute stress and posttraumatic stress disorder.” (p. 1542)13 Our results indicate that a broader and more nuanced definition for delirium-related distress is required. For example, we found that delirium-related distress involved aspects of depression, anxiety, stress, and frustration, with long lasting effects. Of note, earlier definitions lack fear, which in our review was found to be a common attribute and consequence of delirium-related distress. We have also shown that lack of prior knowledge of delirium and stressful hospital environments can worsen related distress.

Importantly, family and friends brought comfort and feelings of safety to the patient. However, family visiting could also be distressing when relationships were strained or patient’s behaviour changed.39 Similarly, while the presence of nurses could be increase patients’ feelings of safety, this was not the case when nurses had been a feature of the patient’s hallucinations.42 Our study highlights the value of engagement with families and listening to patients, as patients reported that they valued supportive staff and being able to talk about their experience. This aligns with previous research highlighting the importance of kindness and empathy for patients and their families.10

Empirical referents reported in the results were measurement tools focused on aspects of delirium, not specifically on the aspects of delirium-related distress discussed in this study. The Delirium-O-Meter76 was the only measure included identified in this review with an item related to delirium-related distress; namely, ‘anxiety/fear’ in the carer version. Based on the findings of our review, future measures of delirium-related distress could include domains such as fear, depression, stress, anxiety and frustration.

The findings of this concept analysis echo a previous systematic review and meta-synthesis in the ICU setting,10 in which delirium-related distress was described as a whole person experience, with elements of distress being emotional, cognitive, physical and spiritual. Our study extends this finding to the broader hospital setting.

Our review draws attention to subsequent healthcare avoidance and health anxiety, such as avoiding General Practitioner visits and caution taking medication. These behaviours are reported in cancer79 and select mental health conditions80 but less are recognised in delirium and warrant future study.

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review and concept analysis is limited by the lack of antecedents and consequences in the literature. Antecedents were most notably lacking for family carers; and consequences for all groups, as the included studies mostly focused on the immediate emotional experience. The literature on protective factors was scarce for all groups. No studies involving children were found. Further work is needed to clarify these gaps. Another limitation is that this review did not examine cultural differences in the experience of delirium-related distress; as it might manifest and be described differently in different cultures,81 this could be a focus of future research. Similarly, we did not quantitively compare differences between patients with delirium who did and did not experience distress. Quantitative observational studies of the protective factors would inform new interventions.

A strength of this scoping review was its broad inclusion of literature, while the concept analysis method allowed for a structured and in-depth exploration of delirium-related distress. However, the breadth of this review is perhaps countered by less detailed analysis. Some included papers provided only summarised brief descriptions of delirium-related distress and lack of primary data prevented deeper analysis.

In the current review, only 20% of full text papers were screened by at least two authors. Due to the large amount of included literature, as well as limited frame for the review which is part of a doctoral program (KC), it was not possible to double screen every full text paper, which may have increased the risk of random error in the screening process.

Conclusions

This scoping review and concept analysis synthesised 57 studies relevant to delirium-related distress for patients, carers and staff across a range of countries and hospital settings. Antecedents included aspects of the delirium and influence of the hospital environment. Attributes identified were largely psycho-emotional in nature, and consequences involved psycho-emotional effects and health avoidance. Feeling safe through the presence of family, friends and nurses and other hospital staff was identified as a protective factor for delirium-related distress. Future research could attend to building the evidence base for antecedents, consequences and protective factors of delirium-related distress by applying concept analysis methodology to direct accounts from patients, carers and hospital staff. Further studies are required to develop and measure new interventions for delirium-related distress in hospital populations.

Acknowledgements

The team wish to acknowledge the valuable contributions of Sarah Su, Senior librarian at UTS.

Ethics statement

N/A

Funding sources

KC is a recipient of the Research Training Program (RTP) scholarship, provided by the Australian Government Department of Education through the University of Technology Sydney.

Declarations of interests

None

Author contributions

KC – Conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, analysis, writing – original draft, visualisation

MD - Conceptualisation, methodology, validation, writing – review & editing

DD - Conceptualisation, methodology, validation, writing – review & editing

AH - Conceptualisation, methodology, validation, writing – review & editing