INTRODUCTION

Delirium is a serious but under-detected serious complication of illness or injury affecting as many as 25% of hospitalized adults and is associated with short- and long- term negative consequences including increased mortality, morbidity, cognitive impairment and functional decline.1 Up to 25% of patients admitted to a post-acute care unit following a hospital stay experience either a lingering or new-onset delirium.2–5 associated with complications, re-hospitalization and death.6–10

Prior work demonstrated that nurses working in the post-acute care setting of three facilities within a large healthcare network displayed gaps in nursing knowledge, confidence and skills related to delirium prevention, assessment and management.11 To close these gaps, we created a multimodal simulation-based educational program for post-acute care nursing staff to educate them on delirium detection, prevention and care.

BACKGROUND

Nurses play a vital role in detecting, managing, and preventing delirium, especially in post-acute settings where providers may not be continuously on site. Studies have found that delirium is under-recognized by nurses in acute and post-acute care settings.11–16 When staff fail to recognize delirium, necessary steps to address the etiology and implement supportive measures are missed. This can increase the severity and duration of the delirium, ultimately resulting in adverse outcomes.17

There are several publications18–27 in addition to a recent scoping review28 describing programs designed to educate nurses on delirium prevention, detection and management strategies. Most of these programs took place in hospital settings and used a variety of educational approaches including classroom lectures, case study, videos, poster viewing, e-learnings, and simulation. Almost all studies found an increase in nurses’ knowledge and self-reported confidence, but less than half measured the program’s impact on actual clinical nursing practice through chart audits or direct observation at the bedside. Several found an increase in the number of documented delirium screenings performed19,20,29–32 or the number of positive screens identified21,33 after the education. However, only a few studies assessed the quality or accuracy of delirium screening performed, interpreted or recorded by the nurses. Three studies defined an accurate assessment as a correct scoring of the assessment tool (i.e. adding up the components of the tool and scoring the result as positive or negative).31,34,35 Only four confirmed clinical accuracy with an expert observing the nurses’ assessment in real time26 or reviewing documentation of signs and symptoms in written notes and comparing them to the nurses’ scoring on the validated tool.18,26,32

Of all the published works on delirium education for nurses, only two took place in a post-acute care setting. Spear implemented an evidence-based delirium prevention protocol in a skilled nursing facility and found a decrease in incident delirium and patient length of stay with self-reported positive practice changes among both nurses and CNAs.21 Jeong studied the impact of a three-session educational program compared to the distribution of a delirium handbook on nurses’ knowledge, confidence and ability to detect delirium in clinical practice. Nurses’ knowledge improved following use of both the training program and the handbook, but those receiving the educational training program also reported gains in confidence and demonstrated an increased ability to detect delirium as confirmed by a psychiatrist’s review.18 Neither of these two programs incorporated a simulation-based approach, which has been found effective in teaching delirium content, nor measured nurses’ actions in response to a new onset delirium.36

The paucity of reports on effective evidence-based delirium education for nurses practicing in the post-acute care setting creates an opportunity for program development and evaluation. Programs need to focus on increasing knowledge and confidence with the result of achieving a demonstrable integration into bedside practice. This would include accurate identification of signs and symptoms of delirium, prompt notification of a provider and implementation of nursing interventions to support recovery.

This study aimed to describe and compare the changes in (1) nurses’ knowledge and confidence levels related to delirium prevention, detection and intervention (2) nurse detection of delirium during patient care and (3) nurse action taken in identified cases of delirium prior to and following a multimodal simulation-based educational intervention.

METHODS

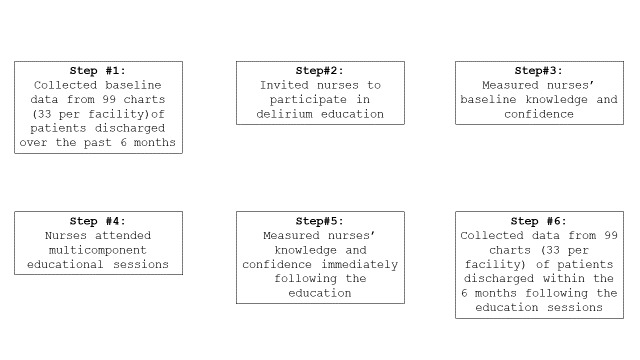

This study took place at three skilled nursing facilities within a healthcare network. The post-acute units within each of these facilities admitted hospitalized patients in need of ongoing care before a transition to home or long-term care. Descriptive data were gathered via a questionnaire completed by willing nurses and a review of documentation found in health records of a random sample of discharged patients. A pre-post design was utilized to measure the impact of education on the nursing staff’s knowledge, confidence and clinical practice surrounding delirium care (Figure 1). Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze results. This study proposal was approved by the Institutional Review Board, which waived written consent from both the nurses and patients.

MEASUREMENT

Nursing Knowledge and Confidence Assessment

All 120 employed nurses in three post-acute care facilities were invited to participate in an assessment which involved completing(1) a demographic instrument reporting years of experience as a nurse, age, ethnicity, and recent formal delirium education (2) a ten question multiple choice delirium knowledge test (3) the scoring of two videos of delirious patients using a validated delirium assessment tool, The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) short form,37 and (4) a five-point Likert scale questionnaire indicating confidence in screening for delirium and notifying a provider of a positive delirium result.

The knowledge test, video scoring activity and confidence scale were administered prior to and immediately following the education. These tools have been previously published.11

Patient Medical Record Review To Determine Delirium Recognition and Related Actions

A retrospective review was done on 198 randomly chosen paper and electronic health records of discharged patients (99 discharged within 6 months prior to intervention and 99 discharged within 6 months post intervention). This number of records was based on power calculations (effect size of 0.34 using 2 degrees of freedom Chi-Square test with a significance level of 0.05) to detect a change in nurses’ delirium detection rates from baseline following an educational intervention. Using CHART-DEL,38 a validated tool to recognize delirium through record review, the researchers identified patients who experienced delirium during their post-acute stay. These records would then be used to explore the nursing staff’s performance around identifying an acute mental status change and acting upon it according to accepted practice guidelines. A detailed description of the process (eligibility criteria and record selection) has been previously published.11

Actions taken by nurses in response to a nurse identified delirium were categorized as appropriate vs inappropriate. Appropriate actions were consistent with published best practices to address the etiology of delirium or mitigate the negative outcomes associated with delirium. Inappropriate actions included failure or a delay to act consistently with published delirium care guidelines.39

EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION FOR NURSES

An overview of our curriculum is described in Table 1. Our curriculum was developed through the application of Kern’s Six-step Approach to Curriculum Development40 (see Supplement #1). Learning methods included passive learning through a power point presentation, active learning through a case study, and experiential learning through a simulation using a standardized patient (see Supplement #2).

RESULTS

A total of 114 of the 120 invited nurses from the three post-acute units participated in components of the delirium education intervention. The nurses were primarily Caucasian females with reported ages spanning five decades. Demographic data is included in Table 2. Few (5%) reported having received any formal education on delirium outside the work setting within the past three months, such as attending a conference or reading a publication.

The following results describing nursing knowledge, confidence and clinical performance prior to and following the education are summarized in Table 3. Pearson Chi-square was used to analyze differences between pre and post intervention performance with a p value of < 0.05 considered to be significant.

Nurses’ Knowledge of Delirium Prevention, Screening and Management

Each of the ten test questions were analyzed individually. Scores improved significantly on seven of the 10 multiple-choice knowledge questions following the education at p<0.05. The remaining three questions also showed improvement without statistical significance.

Nurses’ Ability to Identify Delirium in Video Demonstrations

The nurses viewed two videos of delirious patients and scored them as delirious or not delirious using a validated delirium assessment tool, The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) short form.37 Video #1 (hypoactive delirium with visual hallucinations) was scored correctly as CAM positive/delirious by 97.3% of the nurses before education and 100% after education. Video #2: (hypoactive delirium superimposed upon mild cognitive impairment) was scored correctly as CAM positive/delirious by 45.9% of the nurses before education and 64.9% after education. Neither of these pre-to –post score differences were statistically significant.

Nurses’ Confidence in Delirium Screening and Notification of Provider

For the purpose of analysis, the five-point Likert scale questionnaire responses were grouped into two categories; not at all confident or a little confident versus moderately, very or totally confident. Before the education, 31.9 % of the nurses reported feeling moderately, very or totally confident in screening for delirium. This response significantly increased to 92.0% after education. Similarly, before education, 54.0% of the nurses felt moderately, very or totally confident notifying the provider of a positive delirium screen, significantly increasing to 95.6% after education.

Recognition of Delirium in Clinical Practice

In the pre- intervention patient record sample, nursing documentation was the source of delirium determination by experts using CHART-DEL in 15 of the 22 cases of positive delirium. Nurses correctly identified six of the 15 (40.0%) but missed nine of the15 (60.0%) of these delirious cases. Of the nine missed cases, three (33.0%) had pre-existing dementia. In the post-intervention patient record sample, 15 of the 19 delirious cases were identified by experts by reviewing nursing documentation using CHART-DEL criteria. Of those 15 cases, nurses correctly identified five of the 15 (33.0%) but missed 10 of the 15 (67.0 %) of these delirious cases. Of the 10 missed cases, two (20.0%) had pre-existing dementia.

Nursing Actions

Nurses took appropriate action in five of the six (83.0%) delirium cases they recognized in the pre-intervention period, and in four of the five (80.0%) cases in the post-intervention period. Two of the five (40.0%) pre- intervention cases with appropriate action included immediate notification of the provider by the nurse, where three of the four (75.0%) post-intervention cases included provider notification.

DISCUSSION

Nurses’ scores on delirium knowledge tests and self-rated confidence surveys improved significantly following participation in a multifaceted delirium education program. Efforts to assess the translation of this knowledge and confidence into practice in this study were not successful due to the small number of charts containing signs and symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of delirium documented by a nurse.

This study found a 20% delirium prevalence rate among the combined pre and post intervention chart sample, consistent with reported findings confirming that delirium is common in the post-acute population.2–5 The nurses’ knowledge and self-reported confidence gaps reported in the pre-intervention period were similar to other published findings and support the need for comprehensive and focused delirium education for nurses in the post-acute care setting.5,14,18,21

Nurses achieved low scores in both the written test and the video scoring related to assessing for delirium superimposed on dementia (DSD). This is consistent with other studies which have identified DSD recognition as both a challenge and deficiency among nurses.13,14,41

We attempted to measure the nurses’ uptake of knowledge as it relates to clinical integration, addressing the age-old concept of a theory practice gap. This is described as a dichotomy between theoretical understanding and practical dimensions of nursing first evident in the era of Florence Nightingale.42 Although unable to establish a significant change from pre to post, the one area of clinical improvement seen post-education was a trend toward more nurse to provider reporting of new delirium symptoms. This was consistent with the nurses’ self-report of increased confidence in notifying the provider of a positive delirium screen.

A systematic review of educational interventions to improve recognition of delirium found formal interactive teaching with enabling and reinforcing strategies to be the most effective method.43 Potential barriers to learning and implementing high quality and consistent delirium care were identified. We then integrated content into our educational program to promote success. Studies have shown nurses fail to prioritize delirium assessment and actions in clinical care.44,45 Our educational program incorporated a rationale for prioritizing delirium prevention and screening by highlighting the negative short and long term health outcomes associated with delirium. It also provided a roadmap for nurses to be able to implement positive delirium prevention strategies while avoiding potentially harmful missteps. We chose to reinforce the use of the CAM which was already present in the admission documentation, rather than introducing a new delirium screening tool. We focused on improving accuracy and consistency of delirium assessment and appropriate response to a positive finding. Acknowledging that nurses may perceive time constraints as a barrier to conducting and documenting a proper delirium assessment and plan ,46 nursing staff gave input as to the most convenient location in the medical record to place the twice daily CAM assessment documentation. We also provided supportive resources, such as a Delirium Care Pathway (see Supplement #3) and Delirium ISBAR (see Supplement #4). Providers did not participate in the onsite multifaceted delirium education due to their sporadic schedule at the facilities. A brief overview of evidence-based delirium care and the goals of the nurse focused educational program was presented at a medical staff meeting and providers were given a Delirium Care Pathway.(Supplement #3)

To our knowledge, this is the first delirium education program carried out in the post-acute setting evaluating the impact of a simulation experience on the nurses’ knowledge, confidence and clinical performance of delirium detection and appropriate action. There are limitations to be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. The chart documentation utilized to interpret the impact of the education on nurses’ clinical care could potentially have been done by nurses who did not receive the education, either choosing not to participate or having been hired during the study period. We relied on nursing documentation from the eligible15 charts in each of the pre and post-intervention periods to analyze and draw conclusions regarding the impact of the educational intervention, which were inadequate for statistical analysis. Nurse performance was observed and critiqued during simulation but not on actual patients at the bedside. Future studies should focus on both observation of nurses’ clinical practice and documentation surrounding delirium identification and subsequent actions.

CONCLUSION

This study showed an increase of delirium knowledge and confidence scores among nurses practicing in the post-acute care setting following a multimodal educational intervention. Delirium superimposed upon dementia emerged as a topic requiring further education. An inadequate sample size of delirium positive records made it difficult to determine the education’s impact upon delirium recognition and subsequent appropriate actions by nurses in the clinical setting. There was a trend toward increased provider notification following the education in cases of delirium recognized by nurses. Further studies are needed to identify successful educational models for teaching and embedding delirium best practice strategies into clinical practice in post-acute care.

Acknowledgements

Laura Dzurec; Kathy Fortier; Karen King; Nicole Libbey; Christopher Madison; Janele McAdams; Sheila Molony; Anna-Rae Montano; Jamie Rubenstein

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology CW, JC, TN, SG

Formal Analysis JK, JC

Interpretation JK, JC, TN, SG, CW

Writing- original draft preparation JK, CW, SG

Revising and editing JK, JC, TN, SG, CW

Ethics Statement

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Hartford Healthcare IRB.

Funding Sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Interests

None of the authors declare any conflicts of interest.