Introduction

Delirium is an acute neurocognitive disorder characterized by confusion, inattention, and altered levels of consciousness.1 Delirium affects between 6-38% of older patients in emergency departments (EDs).2,3 Despite its prevalence, delirium remains unrecognized by emergency clinicians in a staggering 86% of instances.4–9 Health information technology, particularly through Electronic Health Records (EHRs), offers promising tools to enhance the diagnosis and management of ED delirium. Modern EHR systems, which have become increasingly interoperable, allow for the integration of customizable applications such as delirium screening tools, order sets, and monitoring systems. This review describes practical EHR-based strategies for delirium screening and management, drawn from institutions with experience implementing such initiatives, to inform health systems developing ED delirium care programs.

Understanding the Quality Gap

Most United States (U.S.) hospitals and EDs do not routinely screen patients for delirium.10 This is an important quality gap. Prolonged exposure to emergency settings correlates with an increased risk of delirium.11 Unrecognized delirium increases the risk of complications and death within the first week after an ED visit.12 Those who develop delirium in the ED or hospital face a twelve-fold increase in the odds of being newly diagnosed with dementia in a year.13 Systematic screening improves the detection of delirium over clinician gestalt.2 For example, a multicenter study of almost 1,500 older adults in Canadian EDs revealed that 50% of delirium cases were missed when relying solely on clinician gestalt.12 However, ED staff report multiple barriers to delirium screening and care, including time constraints and usability of screening tools, within the complex, chaotic, pressured ED environment.14,15

Facilitating delirium screening: A Potential Role for EHR-Based Tools

EHRs can facilitate delirium screening through prompts, alerts, and other notifications.16 One implementation study found that an EHR notification column improved delirium screening rates.14 EHRs can also help couple screening with delirium prevention and management strategies, such as avoiding culprit medications, treating pain, mobilizing patients, and promoting sleep.17 The EHR can also facilitate communication among the healthcare professionals involved in these multifactorial strategies,16 e.g., pharmacists for medication reconciliation, nursing staff for re-orientation and monitoring, technicians for bedside support, and physical and occupational therapists for mobility assistance. While toolkits exist to help EDs implement delirium care programs,17,18 EHR-specific resources are needed for EDs trying to implement EHR-based strategies to support delirium care.

Methods

In May 2021, a group of academic emergency physicians convened to explore initiatives designed to implement geriatric emergency medicine initiatives through two professional organizations within the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM): (1) the Academy of Geriatric Emergency Medicine and (2) the Evidence-Based Healthcare and Implementation Interest Group. At the 2023 SAEM annual meeting, the group of 34 physicians voted to focus on delirium. Subsequent monthly meetings revealed a wide variety in delirium care interventions used at group members’ hospitals, with some EDs having no delirium interventions and others having robust screening and management programs. To assist EDs who were initiating delirium programs, we solicited examples of EHR interventions from robust, sustained delirium intervention programs. Physicians voluntarily provided examples of EHR supports for ED delirium care from five academic institutions, which varied in their geographic locations within the United States. All five EDs pertained to tertiary or quaternary hospitals. Two of the EDs had received Geriatric ED Accreditation by the American College of Emergency Physicians. The group reviewed and discussed EHR-based delirium practices from each site. One member categorized the examples as related to screening, prevention, management, and monitoring of delirium. The group used a consensus process to review categorizations and identify similarities, differences, and themes in EHR-based approaches for ED delirium.

Results

The five EDs’ EHR supports related to:

-

integrating screening tools as EHR checklists

-

alerts and prompts

-

order sets for delirium workup, prevention and management

-

geriatric dashboards

Table 1 provides details about the five contributing EDs and their delirium programs. Table 2 offers highlights of practical EHR-based strategies to facilitate ED delirium programs.

Integrating Delirium Screening Tools into the EHR

All sites integrate validated screening tools as checklists within the EHR, allowing clinicians performing the screening to easily input responses to individual questions required for each tool.

Figure 1 shows integration of the Delirium Triage Screen (DTS), the brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM), and Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (NuDESC) into the EHRs Epic and Cerner. Because the DTS can be performed within seconds, sites incorporate a DTS EHR checklist into triage procedures and initial bedside nursing assessments. Sites also use the DTS as part of a two-stage process, in which a positive screen prompts a more comprehensive delirium assessment, such as the Brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM). For two-stage screening, sites use an automated alert or pop-up to facilitate communication within the care team that a second screening needed to be performed (Figure 2). Selection of which screening tool to integrate into the EHR depends in part on the tool(s) used in the inpatient setting to create continuity and facilitate comparisons in assessments over time.

Provider Alerts and Prompts

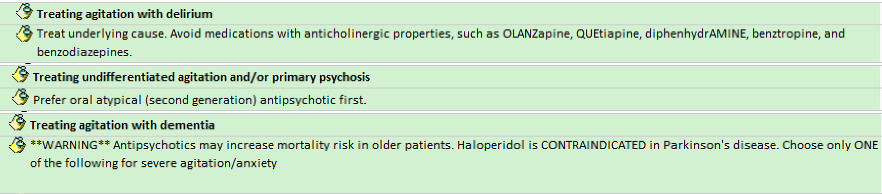

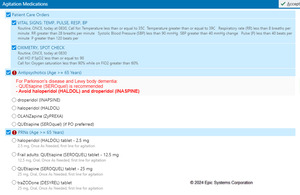

Alerts and prompts are pop-ups in the EHR that provide reminders to clinicians or nudge them to take a specific action. Sites use clinician alerts in several ways. First, alerts can help clinicians take next steps to intervene on a positive delirium screen. One site uses a Best Practice Advisory (BPA) pop-up after a positive DTS screen to prompt ED clinicians to consult the ED pharmacist for delirium medication management (Figure 2). Second, sites incorporate BPAs into clinical decision support (CDS) tools for ED clinicians. As an example, at one site, when clinicians order a potentially inappropriate medication, the EHR triggers an “Older Adult Medication Risk” BPA (see supplement A) alerting the clinician that the medication may pose a safety risk. The ED provider can then cancel the order and choose an alternative medication or override the alert. Language about safety can also be inserted into orders as “warnings” (see supplement B) to avoid medications, such as anticholinergic medication in agitated patients with delirium, or as suggestions for more appropriate medications, e.g., “prefer oral atypical antipsychotics first.”

Order Sets for Delirium Prevention, Workup, and Management

An order set is a pre-defined group of clinical orders in the EHR that help streamline care, such as labs, medications, and consults. Order sets are intended to decrease cognitive burden for clinicians and promote patient safety. Sites employed order sets related to the prevention, workup, and management of delirium. Successful implementation of an order set requires interdisciplinary input on which items should be included in the order set, engagement with nursing and inpatient teams to ensure coordination and sustained therapies across the course of a hospital stay, information systems support to build and test the order set in the EHR, departmental leadership enthusiasm to dedicate staff meeting times to the use of the order set, a clinical champion to encourage that use, and ongoing monitoring and quality improvement. Below, we summarize key elements sites included in order sets to balance comprehensiveness and usability.

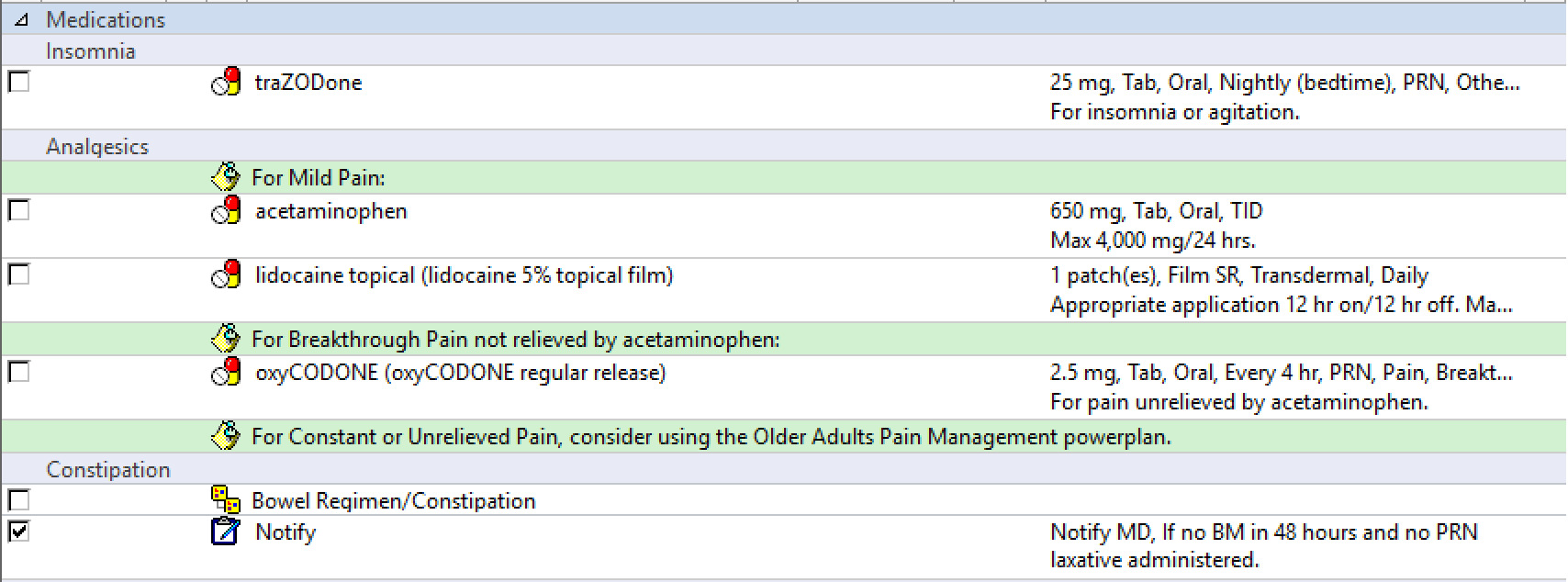

Delirium Prevention. Based on available resources, the five institutions employ delirium prevention orders for all older adults vs. for specific older adults at high-risk for ED delirium (e.g., those with dementia, those who speak a non-English primary language). Delirium prevention activities rely most heavily on nurses and relate to optimizing patient mobility, comfort, and communication. Prevention order sets can be used by all clinicians. Orders related to patient mobility include ambulating patients during each shift, getting patients out of bed for meals, and helping reposition patients with limited mobility every few hours. Orders related to patient comfort can include dimming lighting during evenings and overnight periods, giving patients sleep masks, specifying hours that patients should be allowed uninterrupted sleep, and performing bladder scans, which are particularly useful in patients with difficulty communicating toileting needs. Orders related to minimizing tethers, such as telemetry and oximetry wires can promote both patient mobility and comfort. As patients may not have corrective lenses or hearing aids with them in the ED, providing hearing assist devices and reading glasses can facilitate communication with the healthcare team. As pain and constipation can contribute to delirium, order sets can prompt standing doses of acetaminophen and lidocaine patches, which generally have few contraindications, as well as stool softeners (see supplement D).

Delirium Workup. Sites use order sets after a positive delirium screen to prompt a medical evaluation for potential underlying causes. Medical evaluation orders include routine laboratory tests to evaluate for metabolic derangements as well as urinalysis/culture, COVID testing, and chest X-ray to evaluate for potential infectious etiologies (see supplement C). Sites’ order sets also include options to consult pharmacy (for medication review and recommendations on modifying high-risk medications like benzodiazepines) and/or geriatrics, psychiatry, or neurology to help ED teams investigate the cause of delirium. Sites vary in the comprehensiveness of medical workup and specialty consultations suggested. At one institution, delirium orders are grouped into an “ED fever/sepsis/altered mental status/delirium” order set, which has broader diagnostics than the aforementioned.

Delirium Management. For patients in whom delirium is identified, sites’ order sets focus on specialty consultation and agitation management. Specialty consultation orders for delirium management include (a) physical and occupational therapy, for recommendations regarding mobility and activities to redirect fidgeting behaviors, to reduce delirium duration; and (b), geriatrics, psychiatry, or neurology, depending on hospital system resources. Order sets also contain medications for management of severe agitation with geriatric-specific dosing and warnings about the risks of anti-dopaminergic agents, e.g. haloperidol and droperidol, in persons with Parkinson’s Disease and/or Lewy body dementia. Some order sets trigger an expanded warning message if a clinician chooses medications considered high-risk (see supplement E).

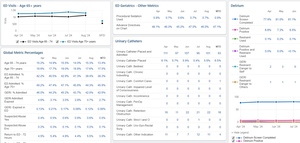

ED dashboards

An EHR dashboard is a visual tool that displays real-time data on clinical processes and can enhance patient care through data access and management. Dashboards allow for real-time data visualization, CDS, user-centered design, and performance monitoring and feedback.19 They provide functionalities like detailed reporting, customization to meet specific needs, alert creation for critical situations, resource management, and real-time information display.20 Dashboards make compliance monitoring possible, i.e. evaluating for adherence to clinical guidelines, regulatory standards, and patient safety protocols, which is integral to the delivery of high-quality, patient-centered ED care. Compliance monitoring involves training, continuous data collection and analysis, enabling real-time tracking of adherence to clinical guidelines and safety protocols. Dashboards and real-time monitoring systems can be used to identify and address deviations from protocols, regular reporting, identifying trends, and areas for improvement thereby minimizing the risk of adverse events (see supplement F). This process fosters a culture of continuous quality improvement and informs initiatives aimed at enhancing patient outcomes and care delivery processes.

In one of the sites that has received geriatric accreditation, a dashboard is used to ensure that staff members consistently adhere to the established screening procedures. The dashboard enhances communication and information exchange among team members regarding positive screening results. Effective communication is crucial for timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Sites do experience challenges implementing ED dashboards to track delirium screening. Ensuring data quality and reliability is crucial but often difficult. Integrating dashboards with other hospital systems can be complex and making sure the functionalities meet the diverse needs of ED staff requires careful planning. Additionally, protecting patient confidentiality while displaying information on dashboards is a critical concern.

Discussion

We report here how 5 EDs use EHR to facilitate screening, prevention, and management of delirium. EHRs facilitate screening, preventing, and managing delirium through BPAs and order sets that reduce cognitive load for clinicians and standardize care by providing CDS tools. This work also emphasizes the importance of the EHR in coupling positive screening with interventions, as screening alone does not change the outcomes for patients with or at-risk for delirium.21 Compliance monitoring using dashboards provides real-time feedback and tracks adherence to clinical guidelines, facilitating continuous quality improvement. Implementing these strategies can help manage and mitigate delirium in EDs, with a goal of ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Several of the strategies we describe are supported by prior research and scholarship. Using the EHR to implement screening has been shown to improve ED delirium detection rates.22 One program describes using an EHR Best Practice Advisory (BPA) to alert an ED provider if high-risk delirium status is identified.23 Delirium prevention and management order sets include items such as hearing assist devices and reading glasses, which can facilitate communication with the healthcare team.24 They also contain orders for physical and occupational therapy, which have been shown in the ED to reduce delirium duration.25 Dashboard-based audit and feedback has been used in medication safety programs for older adults,26 clinical guidelines implementation and standardization of care for chronic medications27 like antihypertensives, and monitoring bundles for postoperative delirium.28 Dashboards play a vital role in enhancing process control, communication, and overall management in ED.20

Despite the promise of these EHR-based tools, gaps in evidence remain. It is unclear which screening tool is optimal for EHR integration; this decision may be health system dependent. A recent systematic review of ED delirium screening instruments concluded that while the 4AT has been studied the most in the ED, other screening instruments may be more sensitive or specific in ruling out or ruling in delirium, respectively.29 Selection of delirium screening tools for order sets depends on if the goal is to rule in or rule out delirium. Studies are lacking regarding the impact of EHR interventions on ED delirium duration. Little is known about how order set design affects clinician adherence, or whether specific components (e.g., antipsychotic alerts) improve patient outcomes. There is also limited evidence about use of the EHR to facilitate targeted, rather than universal ED delirium screening. Some EDs screen all older adults above an age threshold,30 whereas others identify individuals at greatest risk of delirium based on age and geriatric syndromes.23 Future research is needed to evaluate which EHR elements most effectively link screening and intervention, which elements clinicians value the most, and which elements are most transferable and sustainable in diverse ED practice settings.

Most sites represented herein are academic, urban, and relatively well-resourced, with institutional support–including informatics resources–for geriatric care. Using EHR-based tools to support ED delirium initiatives requires several institutional resources, such as educational materials, frontline staff time, and EHR informatics support.31 For lower-resource EDs without dedicated infrastructure for geriatric care, implementation of a basic order set—designed with local workflows in mind—may represent a starting point. Local champions of the order set may focus on elements that do not require specialist consults or additional staffing. Medication-focused BPAs may also be a relatively lower-effort, high-impact change. Sharing modular and adaptable frameworks, we have done here, can help lower-resourced EDs prioritize incremental steps towards improving delirium care.

Limitations

This review is based on examples shared through a discussion-based, multi-institutional working group rather than a systematic survey. While this limits generalizability, it allowed for in-depth exploration of implementation strategies at each site. The five contributing sites are academic, urban, and largely tertiary or quaternary centers, each with institutional interest in geriatric care. Thus, findings may be less applicable to lower-resourced EDs. While Epic and Cerner are the most widely used EHRs in the United States, transferability to other platforms, such as Meditech or CPRS, may be constrained by differences in customization and interoperability. Finally, while these tools are promising, their direct impact on clinical outcomes remains untested and should be explored in future research.

Conclusions

EHR-based tools offer promising strategies to improve delirium screening, prevention, and management in the emergency department by standardizing workflows and supporting clinical decision-making. Our real-world examples illustrate feasible approaches but underscore the need for adaptions across varied clinical settings. Future research should evaluate the impact of these tools on patient outcomes and explore implementation in lower-resourced environments.

Acknowledgements

none

Author Contributions

AC, LTS, MK, SL, RMS, SWL contributed to concept. AC, AB, AP, KS, SWL, RMS, LTS, MK, AF, AP, KS, and FB provided types of delirium tools. All authors helped write or edit the manuscript.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for this study as it involved the analysis of electronic health records and systems without any patient involvement.

Funding Sources

RMS was supported by research grants from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) (R33AG058926, R03AG082923, and R21AG084218) and SAEMF/EMF (GEM2023-0000000008). ANC receives support from the NIA (R03AG078943) and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Foundation. ANC and AB receive support from the Houston Veterans Administration Health Services Research and Development Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety (CIN13-413). LTS was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) K23AG061284. SWL received support from West Health/John A. Hartford Foundation. ABF receives support from the NIA (5-R03-AG078933 and 1-K23-AG080061) and Emergency Medicine Foundation.

Declaration of Interests

Nothing to disclose.

.png)

.png)

.png)

_triggered_for_positive_delirium_triage_screen.png)

_older_adult_medication_risk.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

_triggered_for_positive_delirium_triage_screen.png)

_older_adult_medication_risk.png)