Background

Delirium is an acute deterioration of mental functioning characterised by fluctuations in attention and cognition.1,2 It affects 10-18% of hospitalised patients and is likely underreported.2,3 Delirium is precipitated by myriad factors including infection, medication and falls. Pre-existing cognitive, sensory impairment and advanced age increase vulnerability, though a cause is not identified in a third of cases. Delirium is associated with adverse prognostic outcomes and healthcare burden, with older people with delirium occupying approximately 41% of inpatient beds nationally.4,5

Delirium is also associated with detrimental outcomes including doubling length of inpatient stay (LOS), increased incidence of complications and increased risk of institutionalisation.6 Furthermore, delirium is independently associated with increased mortality, conferring a higher mortality rate than both sepsis and myocardial infarction.7 Even high baseline cognition does not confer protection against elevated mortality associated with delirium.8

Delirium also imposes substantial economic burden, estimated at $AU8.8 billion annually.9 The aged population in Australia is projected to increase by a factor of 2.3 over the next decade, with the prevalence and consequent costs of delirium expected to rise in parallel10,11 (see Figure 1). This presents a clear economic incentive for developing and investing in effective strategies to address delirium.11

Despite this impetus for combating the rising prevalence of delirium, there is limited evidence to guide Australian hospitals.12 The current approach appears guided by consensus opinion and includes education, comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), family partnerships and multidisciplinary engagement.13 Overseas, there is increasing interest in novel paradigms involving the integration of medical, specialist geriatric and psychiatric teams in delirium management. The TEAM trial in the UK demonstrated that caring for patients with delirium in a combined Medical and Mental Health Unit was a cost-effective intervention that increased quality of care and improved patient and carer satisfaction.14 Changes in mortality and LOS were not demonstrated.14–16 There are also current attempts to shift delirium management to a community setting utilising a similarly skilled team.17

Despite promising trials overseas, few studies have focused on the Australian context. In September 2021, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care released eight quality statements to comprise the Delirium Clinical Care Standard incorporating guidelines from NICE and SIGN 157 guidelines.1,18,19 The statements include early identification, prevention, patient-centered care, treating underlying causes, avoiding antipsychotics and appropriate transition from hospital care.19 To achieve such diverse standards, involvement of multidisciplinary teams will be essential. This scoping review will explore the existing evidence for integrated multidisciplinary teams in detection, prevention and treatment of delirium in the acute inpatient setting in Australia.

Objectives

Despite guideline development and consensus support for interdisciplinary approaches, there is a lack of robust research to guide evidence-based practice in Australia. The current review therefore aimed to identify and synthesise existing Australian literature on the use of integrated team approaches in identifying, preventing and treating delirium.

Methodology

The review was guided by the PRISMA scoping review framework, utilising the steps outlined. Scoping methodology was selected to identify knowledge gaps.20

Eligibility criteria

Primary research data, descriptive studies and meta-analyses examining outcomes of integrated, multidisciplinary care in managing delirious elderly patients were included. Inclusion criteria comprised English language, patients aged 65+ years old, Australian studies and a publication date between 2011-2021. Exclusion criteria included studies related to dementia, prospective studies, duplicate studies and studies based in a community setting. Eligible papers were tabulated using Microsoft Word.

Information sources and search strategies

Databases searched included Medline, PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Health Policy Reference Centre, Health and Behavioral Science, Embase, Cochrane, CKN Discovery, Google Scholar and grey literature, with subsequent snowball methodology.

Selection process

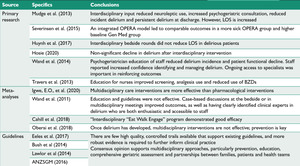

Forty-seven papers were identified and cross-checked by two key investigators. Following review, thirteen papers were deemed suitable for inclusion (see Figure 2).

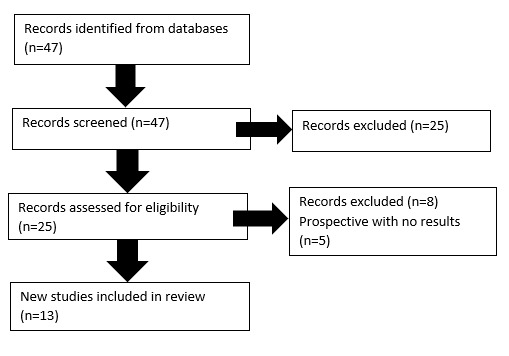

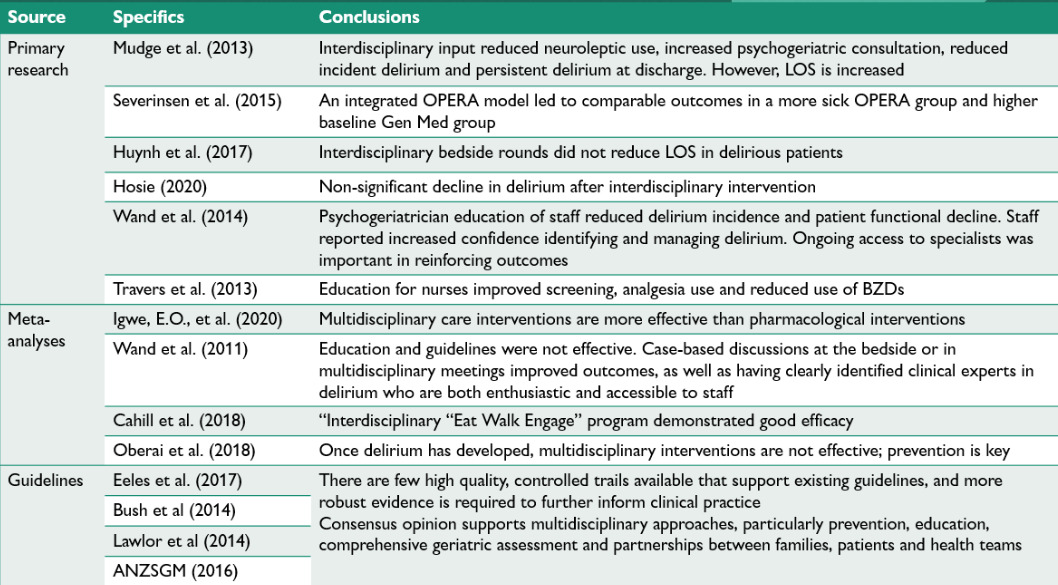

The papers meeting criteria were tabulated; see Figure 3.

Data collection process

Key findings were recorded and grouped according to study type. The key investigators worked collaboratively, allowing cross-checking of recorded findings (see Appendix A).

Data items

Given the breadth of study design included in this review, the outcome measures varied considerably. Common measures included LOS, trajectory of delirium and associated healthcare costs.

Study and reporting risk of bias assessment

The investigators developed a consistent review strategy using the CASP checklist, then worked independently to review all papers. The findings were then merged to reduce assessor bias.

Effect Measures

Outcome measures considered included LOS, delirium incidence, mortality, medication usage, re-admission and discharge to residential aged care facility.

Synthesis methods

Results were tabulated and grouped according to study type (see figure 3).

Certainty assessment

Statistical power of each study was considered where applicable.

Results

Thirteen papers met criteria for inclusion and were divided into; primary research, meta-analyses or review articles and descriptive papers focusing on guideline development.

Primary studies

Six primary studies met inclusion criteria. Four identified the impact of a multidisciplinary approach, while two studies focused on evaluating educational programs about delirium.

Mudge et al.21 conducted a year-long RCT at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, examining patients aged sixty-five years plus who were either at risk or diagnosed with delirium. They developed multidisciplinary strategies including routine screening for risk factors, detection tools and education. These interventions were delivered to one medical ward, with another ward acting as a control. This recruitment method prevented true randomisation or blinding.

Results showed a statistically significant reduction in delirium at discharge in the intervention group (p=0.016), and no incident cases of delirium despite 44% of patients being identified as at-risk.21 Additionally, the intervention group received increased psychogeriatric consultation and fewer neuroleptic drugs. Interestingly, the intervention group had increased mean LOS compared to controls (P=0.01). These findings are limited by the short post-discharge evaluation phase of just four months.

Severinsen et al.22 also analysed outcomes of patients admitted under a multidisciplinary specialist team compared to care-as-usual. The retrospective clinical audit methodology prevented random allocation or blinding. Patients aged over seventy-five years admitted under General Medicine were compared to an Older Person Evaluation Review and Assessment (OPERA) model. The study aimed to validate the multidisciplinary care needs of older patients requiring acute hospitalization.22The authors reported that OPERA patients were significantly more unwell by Charlson Comorbidity Index scores and more likely to have a diagnosis of delirium and dementia at admission. However, the mean acute LOS, readmission and mortality rates were similar for both groups. The authors inferred that these similar outcomes in patient populations despite their disparate baseline supported the efficacy of the OPERA model.22

However, while they identified a similar acute LOS stay between groups, OPERA patients had a longer overall LOS with prolonged subacute admission. Although this may reflect the poorer baseline of the OPERA patients, this correlates with Mudge et al’s21 finding that interdisciplinary intervention increased LOS. Furthermore, while this study corroborates the value of multidisciplinary intervention, the study design is limited. It was a single institution study with small sample size (n=134 in each group), which may have reduced power and increased risk of type 2 error. It also used an age cut-off of 75 years compared to the more common 65 years and over, reducing generalisability.

In contrast to the previous papers, Huynh et al. (2017) found no benefit to incorporating structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds, rejecting the hypothesis that this may reduce delirium rates, LOS and mortality. It is possible that the limited outcome measures failed to capture other potential longer-term impacts of interdisciplinary rounds.23

Hosie et al. (2020) also failed to detect clinically significant outcomes in a phase II pilot study evaluating non-pharmacological measures to reduce delirium incidence in patients with advanced cancer. The intervention comprised six domains; eating, drinking, sleep, exercise, reorientation, vision plus hearing, and family. This study did not achieve its primary outcome of service delivery feasibility, although lack of adverse effect and a non-significant decrease in delirium incidence post-intervention was argued to support the proposed phase III trial.24 One major limitation was that many participants died during the study due to the population characteristics.

Other primary studies have examined the impact of staff education on delirium outcomes. Wand et al.25 utilised a pre and post-intervention methodology to assess the effectiveness of an educational program to prevent delirium in hospitalised older patients. They assessed the impact on delirium incidence, patient functional decline, staff recognition of delirium and staff confidence.25 The study reported a significant reduction in rates of delirium incidence (p=0.042) on discharge, supportive of the education intervention.25

This conclusion must be tempered by analysis that the pre-intervention group was noted to have significantly higher rates of medical co-morbidity than that of the post-intervention group. Reduced incident delirium in the post-intervention group may reflect underlying population differences rather than the intervention. However, the education was highly rated by staff and case-based discussions were found to be particularly valuable. Objective staff knowledge of delirium and self-rated confidence also improved post-intervention.

Travers et al.26 also investigated an educational program designed to improve nurses’ efficacy in delirium screening. This study was conducted across medical and surgical wards of a large tertiary hospital in Southeast Queensland, Australia. Experienced nurses with a special interest in cognitive impairment were invited to train as ‘CogChamps’ and delivered site specific training to peers. Results demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in screening rates for delirium.26 However, the limited three-month follow-up leaves the sustainability of impacts unknown.

Direct comparison of primary studies was limited by significant heterogeneity of patient populations, lack of control groups without randomisation or blinding, lack of full data reporting including confidence intervals, effect size and divergent study designs.

Meta-analyses and review articles

Four meta-analyses were included and together emphasise the importance of appointing clinical experts to provide staff education surrounding early recognition and remediation of delirium risk factors.

Cahill et al. (2018) evaluated the effectiveness of a multidisciplinary delirium prevention program developed at Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital. The program ‘Eat Walk Engage’ consisted of strategies to improve nutrition and hydration, early mobilisation and meaningful cognitive engagement for patients aged sixty-five years and above. Studies spanned over five years across four hospitals in Southeast Queensland. Overall, this program was deemed effective, sustainable and in support of current hospital safety and quality standards (Cahill et al., 2018).

Igwe et al.27 assessed the effectiveness of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to prevent and manage post-operative delirium. Twenty-five papers met inclusion criteria and were assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist. The authors concluded that multidisciplinary interventions aimed at improving clinical care were significantly more efficacious than pharmacological strategies alone. Adequate pain relief was determined to be the only effective pharmacological intervention for delirium.27

Their analysis of nine non-pharmacological interventions demonstrated that screening for delirium, avoiding polypharmacy, geriatric consultation and systematic psychological training led to significant improvement in multiple outcome measures. The authors highlighted the heterogeneity of methods used to diagnose delirium, which may limit the generalisability of results.

The meta-analysis by Oberai et al.18 assessed the effectiveness of multidisciplinary interventions on delirium incidence in patients with hip fractures. Nine papers met inclusion criteria. Consistent themes included early consultation with psychogeriatricians, staff education and proactive preventative measures. Multidisciplinary team structures were associated with reduced delirium incidence. The exigency of early detection and preventative measures was emphasised, as once delirium was established multidisciplinary interventions did not meaningfully alter duration or severity.18

Wand et al. (2011) conducted a meta-analysis of education strategies in delirium detection and management and assessed the impact on staff performance and patient outcomes. Nineteen studies of variable design were included. The analysis reported that didactic education and guidelines used separately or in combination were not effective. Case-based discussions either at the bedside or in multidisciplinary meetings improved outcomes, as well as having clearly identified clinical experts in delirium who are enthusiastic and accessible to staff.28 The appointment of specific staff members with a designated educational role was suggested to best facilitate positive behavioural and organisational changes.

Guidelines

In the absence of vigorous primary research, current guidelines rely on face validity and consensus support. Eeles et al.29 review of the Australian Delirium Standards and The Australian and New Zealand Society for Geriatric Medicine Position Statement on delirium (2012) present similar recommendations including multidisciplinary approaches, emphasis on prevention, education, CGA and partnerships between families, patients and health teams. Bush et al.30 convened an interdisciplinary expert panel to review existing guidelines and concluded that more robust evidence is required to inform clinical practice. Lawlor et al.31 outlined an analytic framework with key clinical questions and outcomes to help direct further research in this field. Stakeholders universally acknowledge the need for further robust study designs to inform clinical practice.

Discussion

Although consensus-based guidelines exist, this review has illustrated the scarcity of randomised controlled studies to provide evidence for the prevention, detection and treatment of delirium in Australian inpatients. Synthesis of available studies reveals emerging themes including support for integrated models of care, the importance of accessibility of delirium specialists including psychogeriatricians and the use of CGA. The current evidence base also highlights gaps to guide further research, including the need for uniformity in baseline populations, universal definitions of the older person and delirium diagnosis, as well as the exigency for examining both immediate and longitudinal outcome measures.

Role of interdisciplinary team

Primary and meta-analytic studies suggested that interdisciplinary approaches to inpatients at risk of delirium were associated with reductions in incident cases, persistent delirium at discharge and use of neuroleptics. The impact on longer term measures such as mortality and discharge to institutional care was more poorly delineated. Further cluster randomised interventions such as the CHERISH trial identified reduction in delirium incidence without changes in other hospital-associated complications.32 The primary impact of interventions appears related to delirium incidence rather than outcomes such as mortality, implying a more complex aetiology for the latter.

Furthermore, formal education from both medical and psychiatric experts objectively increased delirium knowledge across multidisciplinary teams and increased uptake of preventative strategies.25,26 This suggests that an interdisciplinary team facilitates better adherence to delirium standards of care including early identification, intervention and reduced use of antipsychotic agents (Delirium Clinical Care Standard, 2021).

Overall, primary studies provided promising findings that the development of interdisciplinary teams delivering a CGA model is correlated with reduced delirium onset in at-risk individuals and improved outcomes in multiple domains. However, this was achieved at the expense of significantly prolonging hospital stay which creates a complex cost-benefit analysis that may preclude uptake. Similarly, the common exclusion of palliative, critically unwell, severely demented and those from CALD backgrounds, may have falsely skewed the results towards positive outcomes.

Role of CGA

Another common theme was the utilisation of CGA as an effective intervention. In adherence with guidelines, aspects of the CGA demonstrated to reduce incident delirium included sensory assessment, pain score and analgesia management, utilisation of family, mobility assessment, early screening, and cognitive scoring. The use of CGA has previously been demonstrated to reduce institutionalization and has been an area of increased research over the past decade.18,33 Ellis et al.34 identified that CGA conducted by an integrated multidisciplinary team increased the likelihood that older patients would be alive and in their own home three months post-admission. This review supports the use of CGA delivered by an interdisciplinary team to scaffold delirium interventions.

LOS and study outcomes

However, two studies suggested that these positive outcomes prolonged admission, with associated healthcare burden. This contradicts the general assumption that improved delirium care will reduce LOS and ostensibly disincentivises multidisciplinary approaches. Reasons for prolonged stay are unclear as full patient characteristics and potential causative differences were not reported. Intuitively, having multiple members of the multidisciplinary team engaging with an individual, particularly in a rehabilitative role, may prolong admission.

However, this enhanced input could facilitate improved functionality in the community, reducing dependence and thus mitigate the need for residential care. A potential reduction in long term complications of delirium was not elicited in this review, likely due to short timeframe of follow up (less than six months for all studies). A more nuanced approach towards LOS as an outcome is therefore required to establish whether changes in LOS correlate with reduced delirium incidence or mitigation of longer-term effects of delirium. Greater longitudinal evaluation and improved characterisation of the patient cohort under study is required to elaborate this relationship. This also highlights the importance of multidimensional evaluation of delirium interventions, with no significant findings in those focusing exclusively on single outcomes such as LOS.

Additionally, several authors identified that even where guideline-led interventions demonstrate positive results, logistical challenges surrounding implementation, transient staffing and unclear economic benefit may preclude their uptake. It is possible that these challenges may be overcome by utilising established local experts (such as psychogeriatricians) and peer education models.

Role of psychogeriatrician

The unique role of the liaison psychogeriatrician in delirium management was supported by this review. Education by a psychogeriatrician objectively increased knowledge and improved outcomes and increased psychogeriatric consultation was associated with lower incidence of delirium FitzGerald and Price.35 This correlates with studies such as the TEAM trial that demonstrated that caring for delirium patients in a combined Medical and Mental Health Unit increased quality of care.14,16 Staff training, education and accessibility of delirium experts was essential in staff confidence and improved care delivery.

The use of geriatricians without specialist mental health input was neither cost-effective nor successful in altering clinical outcomes, demonstrating the paramount role of specialist mental health input.36 This was theorised to increase education, enhance bio-psycho-social perspectives, improve response to co-morbid mental health needs, thereby enabling a more patient-centric approach and improved outcomes. An emerging role of specialist psychiatric input in delirium care therefore requires ongoing evaluation.

Strengths and limitations

There are several limitations in this review, including a lack of longitudinal evaluation within the evidence base. Furthermore, a paucity of available results inhibited comprehensive meta-analysis and determination of effect sizes. There is a preponderance of qualitative data and reliance on consensus opinion rather than rigorous quantitative analysis, limiting the ability to draw statistically supported conclusions. There is a clear exigency for increased RCTs investigating delirium management.

However, there are multiple obstacles associated with delirium research, including a population that is often medically unwell, highly vulnerable and lacking capacity. This creates ethical challenges around consent and complicates follow-up. A tendency for delirium to be made as a retrospective diagnosis, missed or inadequately documented further complicates research methodology.37

Despite these limitations, there are several strengths to the current review. It addresses a novel area with a focus on the Australian health system, increasing the generalisability of the findings locally. Similarly, the use of two independent reviewers reduced risk of bias. Future iterations should aim to establish a review protocol using PRISMA guidelines, and conduct bias testing and meta-analyses where more suitable evidence is available.

Conclusion

In summary, the current Australian evidence base to guide delirium detection and management remains lacking. This scoping review has, however, revealed consistent themes such as the importance of a multidisciplinary multicomponent approach, CGA, team education, the availability of clinical experts and early detection. Future research should focus on validating specific practices for implementation in the inpatient setting. One example, with preliminary supporting data, is the integration of psychogeriatric services as part of a multidisciplinary approach. Ongoing research is necessary to develop and embed evidence-based approaches within the hospital setting.